When he was told that his house had been raided and that the SEBIN was looking for him, he probably thought it was time to finally clear up the doubts once and for all.

He had suspected for some time that a “conspiracy” was brewing against him from deep within the government, as he later claimed in an interview. Perhaps it was best to face the situation once and for all.

Moreover, he was confident that his extraordinary connections with some of the most powerful figures in the government, like Diosdado Cabello, and most importantly, with Hugo Chávez and his family—especially Adán Chávez—made him feel immune to any schemes his enemies within the regime might be plotting.

Fueled by a sense of invulnerability and certain he could fix whatever confusion arose, he made his way to the SEBIN headquarters in Helicoide.

At 4:00 p.m. on November 20, 2009, he entered the office of the police body’s director, Miguel Rodríguez Torres.

He immediately realized he had made a huge mistake.

Due to the alleged commission of crimes outlined in the Organic Law against Organized Crime and the Banking Law, Ricardo Fernández Barrueco (RFB) was detained. Two years and eight months have passed.

From Mercal Czar to inmate: in his own words

According to his own account, provided to El Universal almost a year after his arrest from a cell at the Military Intelligence Directorate in Boleíta Norte, Caracas—where he was transferred from the SEBIN—RFB claims to have been a medium-sized entrepreneur in the agro-industrial sector focused on producing sugar cane, corn, and rice, owning processing companies acquired during Rafael Caldera’s government, such as ProArepa, part of the Agricultural Marketing Corporation.

He mentions that he participated in the privatization process supported by the Venezuelan Investment Fund to acquire two sugar mills. His family owned lands inherited from his grandfather, an immigrant who arrived in Venezuela in 1952 and settled to work in Turén. He also had companies in the fishing sector. However, he admits that his main economic activity was shipping and fishing operations with groups from the United States and Europe, starting as an employee before becoming independent.

He confesses that he did not vote for Hugo Chávez in 1998 (close sources claim that the whole family was staunchly anti-Chávez), but the president “wanted to develop some social programs implemented by Rafael Caldera (Agenda Venezuela) in which he participated as an entrepreneur, and that due to its significant impact, caught the attention of the new President, who adopted and promoted it. The goal was aimed at extreme poverty sectors and was undertaken by the FAN,” he recalls.

The 2002 strike changed everything for Fernández Barrueco. He asserts that it was the government, through the FAN, that summoned his group of companies, along with 64 other entrepreneurs and producers, to face the food crisis. His fleet of trucks was said to be crucial in breaking the general strike of 2002 regarding food supply.

What RFB doesn’t mention are the accusations that circulated about entrepreneurs like him donating large sums of money to the governing party. His contacts in the government included Adán Chávez, whom he met through the former magistrate, now a fugitive, Luis Velázquez Alvaray, and the former Minister of Agriculture and Land, Efrén Andrade. During the regional campaign in Barinas, for instance, in addition to showing up with trucks full of food, RFB bought the newspaper De Frente Barinas to give it to friends of the president’s brother.

According to RFB, in March 2003, he was invited again by the high military command as an advisor for the design of the Mercal program. He justifies the program, labeling it “successful” and attributing the attacks to that situation.

RFB claims to have not received credits, money, or subsidies from the government or the public financial system. He insists that his companies had been audited by U.S. agencies, demonstrating that their growth and funds came from sustained work in the agricultural and industrial areas.

This is contradicted by the Planning and Finance Minister himself, Jorge Giordani, who in his book Impresiones de lo Cotidiano (2010) states that the entrepreneur consolidated himself through operations with public bodies.

Additionally, one of the audits RFB refers to, the FTI from the U.S., claims that he received a promissory note worth $1.8 billion from the Venezuelan government, which he also denies.

In the interview granted to El Universal, RFB avoids discussing the financial activities, which are the official reason for his arrest.

He emphasizes, “There was never any commission payment or intermediaries (in the import and distribution of food). Our activity did not require ‘lobbying,’ and the profit margins are so small that to achieve them, one must work with large volumes and deliver on time with quality and responsibility. In this context, there is no margin for illicit activities.”

To claim that with food imports, especially in a country with exchange controls, there are no possibilities for illegal activities is truly absurd.

Sources close to the pseudo-entrepreneur report that food imports became a financial business for RFB. Like many other importers in Venezuela, overbilling and fraud against CADIVI to obtain dollars at the official rate was a daily and natural occurrence for the former Mercal czar.

He would request dollar quotas in amounts far greater than what he actually needed for food imports, which he “inflated,” and which largely never arrived at Mercal.

He profited from the overbilling and also from the financial business surrounding the exchange rate differential. That is, he obtained large amounts of preferential dollars supposedly aimed at importing food and exchanged them on the black market for double.

In this manner, he accumulated money and power for seven years (2002-2009).

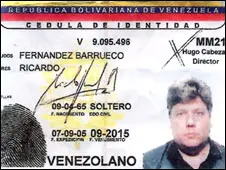

ID of Ricardo Fernández Barrueco

When money isn’t enough

What does a pseudo-entrepreneur with a lot of money and a desire for power do?

Suddenly, between September and October 2009, the then-known “Czar of Mercal” acquired four banks through his business group, which would later be intervened by the national government (Banco Canarias, Banpro, Banco Confederado, and Bolívar Banco), while maintaining food business and selling products to the Mercal network.

The banks in question were bought by RFB for BsF. 400 million each through the brokerage firm Inverfactoring of the InverUnion group, owned by Gonzalo Tirado Yépez, founder of Stanford Bank of Venezuela and a recognized operator and frontman for the chavista bourgeoisie, now a fugitive from justice.

At the time of the intervention of Banco Confederado, the superintendent of banks, Edgar Hernández Behrens, reported that the institution had violated regulations by “granting financing with overdrafts to Fernández” and acquiring participation certificates worth about $283.7 million from Inverfactoring C.A. and Activos Corporativos AG.

Likewise, Bolívar Banco and Banpro also disregarded regulations by financing Fernández with overdrafts and purchasing certificates from Inverfactoring and Activos Corporativos AG for around $269.76 million and $289.76 million, respectively.

In other words, RFB bought Confederado, Bolívar Banco, and Banpro with the banks’ own money, obtained through loans to himself via related companies.

On the other hand, Fernández Barrueco aspired to acquire the telecommunications company Digitel, owned by Oswaldo Cisneros (and his partners Víctor Gill, Diosdado Cabello, and Jesse Chacón), in a deal estimated at $742 million, which was denied on November 18, 2009, by the National Telecommunications Commission (Conatel).

In Impresiones de lo Cotidiano 2010, Jorge Giordani directly addresses his view on the intervention of the banks Canarias, Confederado, Banpro, and Bolívar, along with the arrest of entrepreneur Ricardo Fernández Barrueco.

Giordani wrote: “Since 2008, an action to acquire banking entities has been developing that could not demonstrate the origin of the funds despite their considerable magnitude.” Later in his text, he states that a year later, a serious situation arose that led to “the bankruptcy of the Bolívar Group through the insolvency of the four banks under their aegis.” He comments that “in early December 2009, when many people are ready to start Christmas festivities, around 725,000 deposit accounts in the banks subject to liquidation, the Canarias and Banpro, as well as the nearly 3,000 employees working in the four intervened banks, will have their holiday celebrations ruined by the size of the blunder committed by detained pseudo-entrepreneur Ricardo Fernández Barrueco.”

He further warns about “the lack of transparency of these funds, including the use of depositor resources or other unidentified funds that led to the need to investigate their origin and the deprivation of liberty of the visible head of the economic group, namely Ricardo Fernández Barrueco.”

He acknowledges that this economic group consolidated through operations linked to the public sector. “The investigations undertaken by the Prosecutor’s Office into this problem will allow the case to be brought before the Republic’s courts.”

Strangely, despite recognizing that RFB received government support, that is, from public officials, Jorge Giordani makes no mention of any investigations in that direction. Perhaps because, had he done so, the Prosecutor’s Office would have encountered some uncomfortable names: former treasurer Alejandro Andrade and deputy Pedro Carreño, who placed hundreds of millions of bolivars of public resources in the banks run by the chavista bourgeoisie.

The clearest sign that investigations are only intended to look the other way—specifically at the pseudo-bankers—is that in all cases of the wrongly termed mini-financial crisis of 2009-2010, the Prosecutor’s Office relied solely on the Law against Organized Crime and the Banking Law, without even mentioning the Law against Corruption, when it is evident that without the complicity of high government officials, this “crisis”—more of a macro-scam—would have been impossible to execute.

Ricardo Fernandez Barrueco and his partners

Another look at his origins

Some attribute RFB’s initial support for his businesses to his good relations with political leaders from governments preceding Chávez’s, the truth is that being the son of a humble Spanish immigrant raised in La Candelaria, where his father managed the Hilton Hotel parking lot, he became one of the richest men, not only in Venezuela but also in the world.

Many people know each other in the parking lot of the most important hotel in a city, a meeting point for entrepreneurs and politicians.

There RFB made contact with the son-in-law of the businessman Angel Martín Caloto, owner of Astilleros Santo Domingo in Spain, with whom he established a friendly and business relationship.

He traveled to Spain in the late ’80s after studying economics at the Catholic University, to finalize a deal involving boats from the Benacerraf Group (Banco Unión) with the Calvo Group; thus, he started in the tuna industry.

Later, he obtained a loan to purchase a rice processing plant in Acarigua, Portuguesa state. It was his first successful business.

Though he was a prosperous entrepreneur in 1998, it doesn’t compare to the wealth he would accumulate during Hugo Chávez’s government.

In October 2000, almost coinciding with the beginning of Chávez’s government, Fernández created the parent company that would become the gold mine of his empire. Industria Venezolana Maizera Proarepa was registered with a minimum capital of a single computer worth $1,500.

By 2005, an audit conducted by the Venezuelan subsidiary of KPMG found Fernández Barrueco’s assets to exceed $1.6 billion. His only liabilities were $18,977 owed to SENIAT, by the way.

At that time, he owned 41 companies, mainly in services, agriculture, agro-industry, fishing, forest products, and maritime transport. His agri-food companies were the main suppliers for the Food Mission from the Ministry of Popular Power for Food, through the company Mercados de Alimentos C.A. (Mercal).

In 2008, he bought Nacional Mills and tuna companies in Ecuador. For that same year, his business group, Industria Venezolana Maizera Proarepa, controlled directly or indirectly 270 companies, employed 5,000 people, and owned one of the largest fishing fleets in Latin America, according to an audit by FTI Consulting.

However, Fernández made sure that his name, figure, and businesses went unnoticed. Perhaps due to this obsession with privacy, the press had no photos of him when authorities announced his arrest on November 20, 2009, aside from that of his ID card.

The only public gesture of display known is the initial of his surname on the bow of the vessels in his tuna fleet based in Panama.

Suddenly in 2009, he decided to become a banker.

Initially, he purchased Confederado, Banpro, and Bolívar banks. Later he finalized the acquisition of Mi Banco and Banco Canarias. With these transactions, he became the owner of 5.1% of total bank deposits.

For him, he wasn’t the only one “shopping” financially: Pedro Torres Ciliberto, José Zambrano, and Julio Herrea Velutini were also buying banks, insurances, and brokerage houses left and right.

It was common knowledge; the so-called boliburgueses (at WaC we prefer to call them chavistas bourgeoisie to avoid offending the memory of the Father of the Nation) were determined to control Venezuelan banking.

There are several theories attempting to explain this sudden interest. Some even circulate that it was all part of a government plan to take over the financial system through its operators and frontmen, but ultimately it spiraled out of control.

Seeking to replace some entrepreneurs with others, Hugo Chávez facilitated the rise of pseudo-entrepreneurs of significant size like RFB. The president himself defended Fernández in a March 2006 Aló Presidente. That was the blank check to act.

Citing doubts about the source of funds, as well as non-compliance with a myriad of administrative standards, the government decided to intervene openly in the four banks acquired by RFB: Bolívar, Banpro, Confederado, and Canarias on November 20, 2009.

In the case of Banco Bolívar, authorities ordered “the non-viability of transferring shares in favor of the company Galopy Corporation International NV and its shareholder Ricardo Fernández, for failing to demonstrate the origin of the funds for acquisition and capital increases, banking experience, and financial capacity.”

Doubts about the source of money also extend to Banco Canarias, which by October closing had a capital of 274.2 million bolivars, of which 270 million, that is, 98.5%, “had not been authorized by the Superintendency for failing to show the origin of funds.”

To purchase Banco Canarias, Ricardo Fernández structured a financial scheme where Banpro, despite being prohibited from making investments due to failing to meet solvency ratios, acquired shares of Canarias through a public offering.

On September 29 of that same year, the Superintendency of Banks ordered Banpro to “reverse the purchase operation.”

Self-loans, a specialty of pseudo-bankers

The Superintendency detected that both Bolívar, Confederado, and Banpro were granting “financings through overdrafts to companies belonging to the Ricardo Fernández Barrueco group.” In one of these transactions, recorded by the Superintendency in a memo dated June 26, 2009, Banco Bolívar lent 398.4 million bolivars to Ricardo Fernández’s companies through overdrafts in current accounts.

Due to breaches of reserve requirements that banks must maintain for the eventuality of not collecting delinquent loans, the required equity index, which mandates that private funds represent at least 8% of assets, and liquidity deficiencies, the Superintendency ordered a series of measures which prohibited making investments, among other things.

However, Bolívar, Banpro, and Confederado violated this regulation and acquired participation certificates from the Inverfactoring company for 1.2 billion bolivars and shares from Activos Corporativos AG for 613 million bolivars via structured notes.

It thus becomes evident that, beyond the internal struggles among chavistas—some officials and others operators—whom RFB blames for his misfortune, there were justifiable grounds to intervene these financial institutions and act against those responsible for these serious financial crimes.

It is also indisputable that the government was aware, and some of its members were necessary accomplices in the macro-scam being perpetrated against the nation’s finances.

The financial ties with Cuba

In the last days of June 2012, rumors circulated about a possible amnesty for some imprisoned bankers, including Ricardo Fernández Barrueco.

This possibility was denied by the government.

In RFB’s case, apparently, the intervention of his personal friend Raul Castro, who allegedly sent an envoy to visit him in prison, was close to securing presidential pardon.

The friendship between the two is said to have emerged when Chávez ordered RFB to support the Cuban government in its economic recovery.

For unknown reasons, the Venezuelan magnate was unable to fulfill the assigned mission and as a sign of apology sent a very special gift to the Cuban government through Raul Castro: 28 BMW vehicles.

This information was provided by a former security employee of RFB in Panama to El Nuevo Herald, within the context of a convoluted story of confrontations, betrayals, dirty business, espionage, alleged drug trafficking, and even reports of assassination attempts, which mention the names of RFB and three sinister figures from the Venezuelan government: Pedro Martín Olivares and Hugo Carvajal, intelligence apparatus men of the regime, and the former Minister of Interior and Justice, Ramón Rodríguez Chacín.

Although the statement from the ex-employee named Luis Castro does not contain a definitive accusation against RFB or the others regarding a shooting attack his wife suffered but was aimed at him, his complaint to Panamanian authorities revealed unprecedented and surprising aspects of RFB and his surroundings, such as his connections with the Cuban regime.

Apparently, RFB had a good relationship with ruler Raul Castro and then-Foreign Minister Felipe Pérez Roque. His goal was to pave the way “to be first” when the communist regime disintegrated upon Fidel’s death and Raul took full control.

RFB expected to “capitalize on the purchase of several bankrupt companies in Cuba to inject money into them to revive them,” Castro explained in statements to the Miami Herald.

Yet another interesting detail provided by the whistleblower was the explanation behind the mysterious case of the DEA seizing RFB’s private plane in May 2007 at Fort Lauderdale airport.

According to the former security employee, Pedro Martín allegedly contacted an FBI agent at the U.S. embassy in Caracas and passed false information about an alleged use of the plane to smuggle drugs into the U.S.

Apparently, the original plan of his enemies was to plant drugs on the plane. This scheme failed because the aircraft did not stop in the Venezuelan city where it was to load two kilos of cocaine, Luis Castro recounted.

Moreover, Martín allegedly fabricated a report about an alleged money laundering investigation targeting RFB’s companies through the buying and selling of public debt bonds (known as Bonos del Sur) and the state oil company PDVSA.

Surprisingly for those closely following the battle, Fernández reconciled with Martín a year later at Chávez’s suggestion, according to a source close to Fernández, as reported by El Nuevo Herald in its coverage of the case.

A trial that never comes

The volume of money RFB stole from the nation has yet to be determined, but if we consider the audits of his wealth and infer that they hide black funds, we can deduce that the money embezzled from the country exceeded $1.6 billion.

If Forbes magazine had focused on Fernández— as Miami Herald journalist Gerardo Reyes claims— it would have had to register him among the 500 richest men in the world, alongside Donald Trump.

Despite the magnitude of the crimes committed, two years and eight months after his detention, RFB is still waiting for the trial that will present to public opinion his version of the events and that of his accusers. The trial that will determine his fate. Yet, the government appears to be in no hurry…

In statements to the few people who have visited him in his confinement, RFB confesses to being “going crazy.”

And there’s a lot of time to think in prison… too much time.

What will go through the mind of a depressed RFB, who was once one of the richest and most powerful men in the country?

Who will he think about, to whom will he attribute his misfortune and that of his family? Will he regret the overwhelming ambition that led him to his current situation?

Or will he choose the easy path of blaming others, lamenting the long list of partners, accomplices, friends, among ministers, former guerrillas, ambassadors, and officials who not only won’t visit him and want nothing to do with him but also, whenever possible, contribute to dragging him down further and further…

And that’s because Fernández Barrueco forgot the maxim of the chavistas, dixit Vito Corleone: It’s not personal, it’s just business…