He says that

he separates the wheat from the chaff: if their affections are in certain troubles, they are

matters for each one of them. However, his loyalty, insists Venezuelan businessman José Simón Elarba Haddad, does not waver.

For

example, regarding Raúl Gorrín, president of Globovisión and sanctioned by the

U.S. Department of the Treasury, he states to Armando.info:

“I emphasize the word: my friend Raúl Gorrín.” Or, to point out another example, about

Carlos Erik Malpica Flores, former treasurer of the Nation, former director of Finance for

Pdvsa, nephew of Venezuela’s First Lady, Cilia Flores, and sanctioned by the

governments of Panama and Canada, Elarba bluntly says: “He is quite a

friend of mine.”

But these

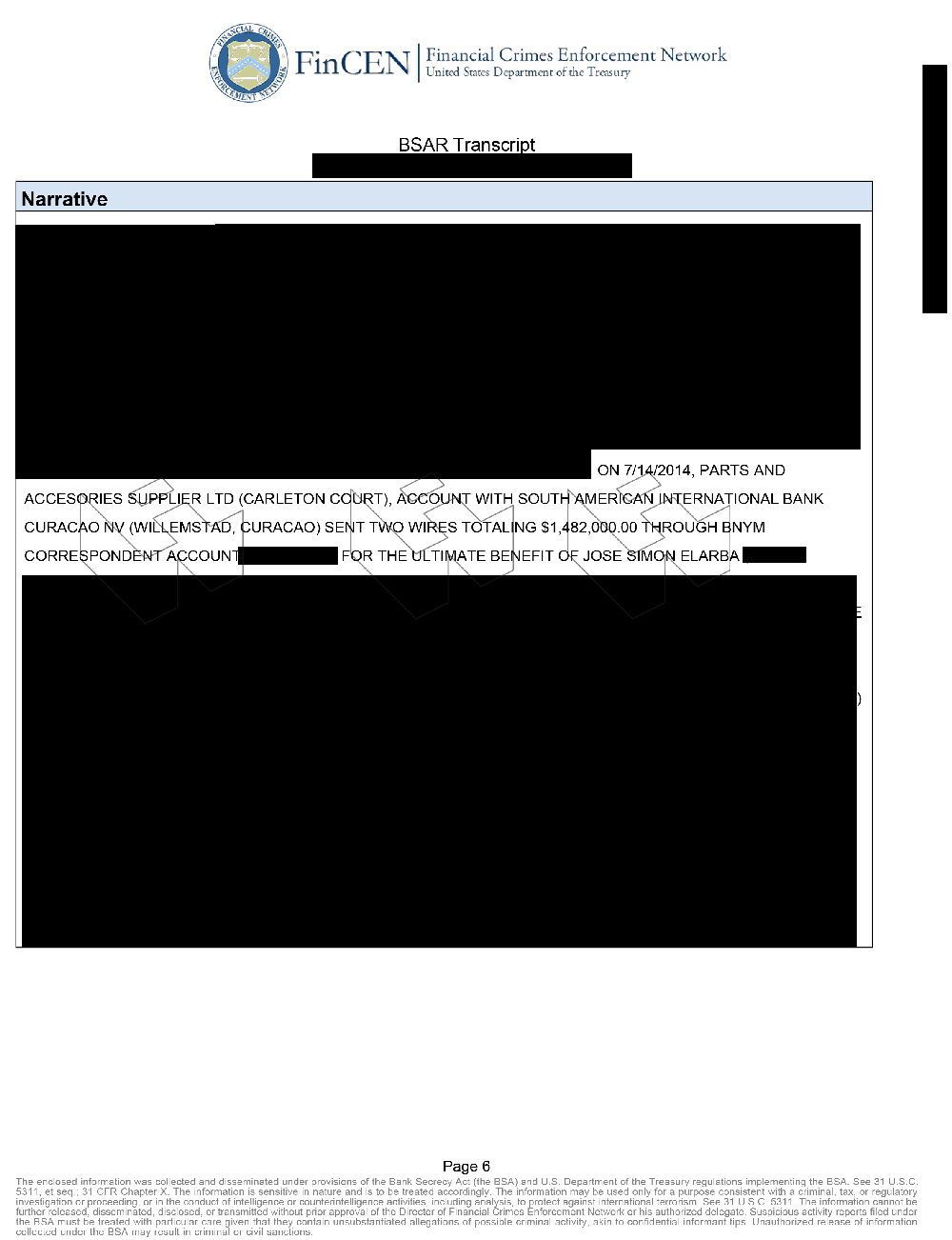

sanctioned friends are not the only ones under scrutiny by authorities in the north. Elarba himself appears in a document

received by the same Treasury Department that sanctioned Raúl Gorrín, including a taxative term: suspicious

activities.

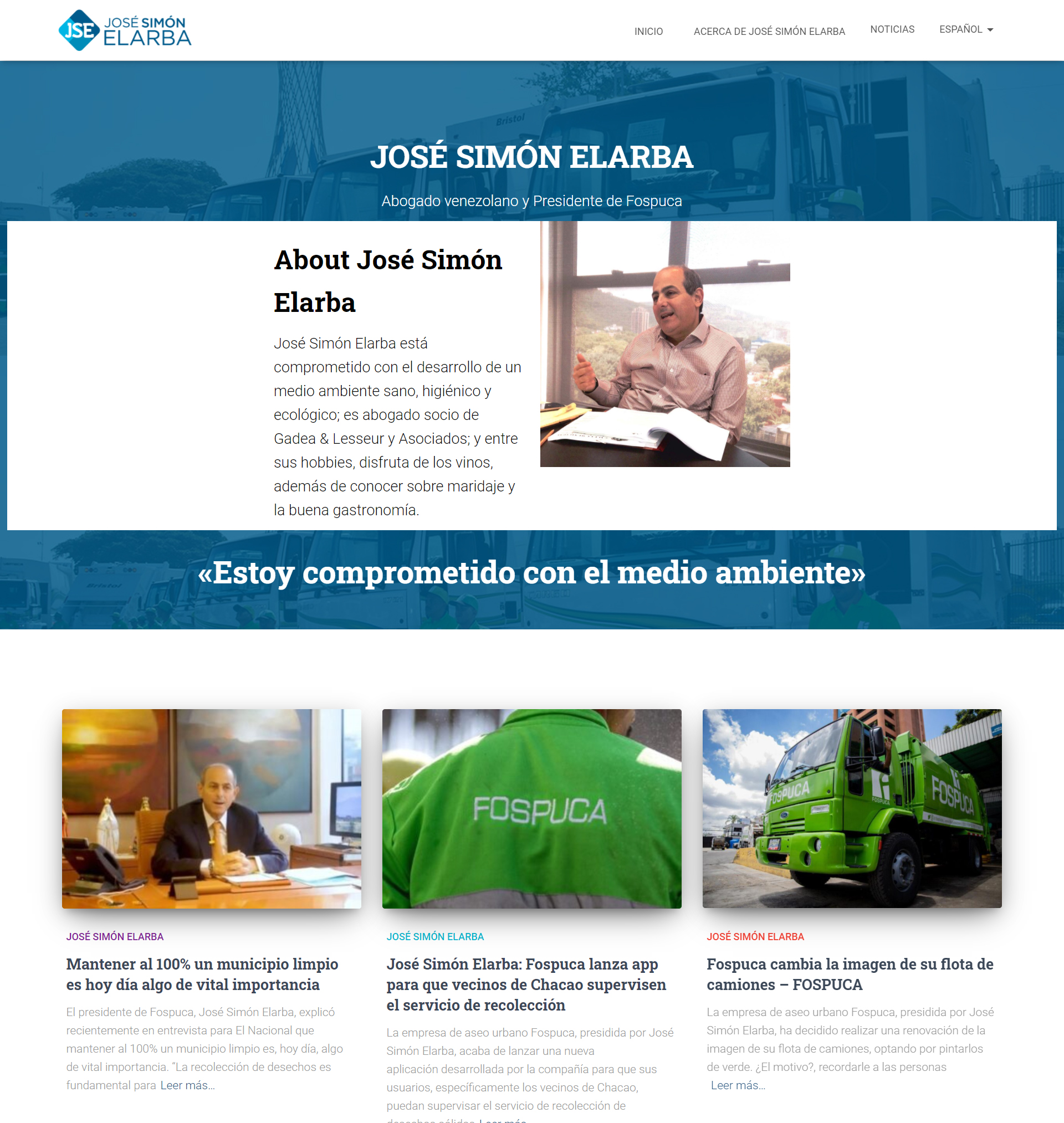

In 2014, the same year of the transfer reflected in the SAR from FinCEN, Elarba purchased Fospuca. Photo: Fospuca.

This

is a Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) contained within the 2,100 documents from the intelligence unit of the

Treasury Department, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), obtained by BuzzFeed News and shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and over 400 reporters in

88 countries, including those from Armando.info, leading to the global journalistic investigation now known as FinCEN

Files.

The

FinCEN Files investigations spanned many cases in Venezuela, including one related to this SAR based on

suspicions regarding the origins of the funds and transactions “without apparent economic, commercial, or legal purposes.” In this case, there is the

transfer of 1.48 million dollars that Elarba Haddad received in one of his accounts in July 2014.

The Sybarite of Recycling

“I am

committed to the environment.” This phrase is part of Elarba’s presentation (Caracas, 1964) on his website, highlighting his role as president of

Fospuca, a company dedicated to garbage collection based in the Venezuelan capital.

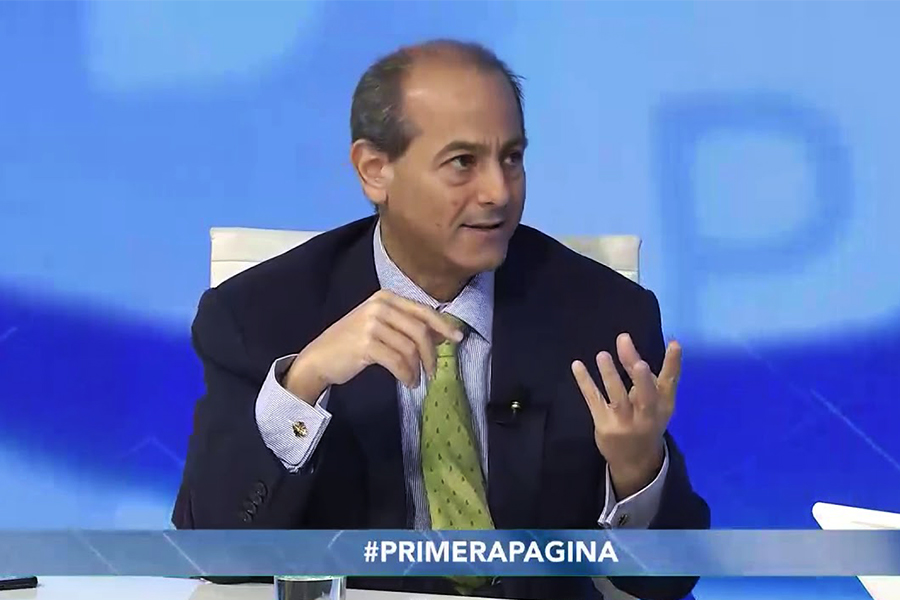

Elarba is a regular guest on interview programs of Globovisión, owned by the sanctioned Raúl Gorrín.

Elarba is a regular guest on interview programs of Globovisión, owned by the sanctioned Raúl Gorrín.

At that

site, he frequently shares news about updates from that private company servicing the municipalities of Baruta, Chacao, and El

Hatillo, all in the eastern sector of Caracas, in the state of Miranda; Iribarren and

Jiménez, in the state of Lara (central-western Venezuela); and, since May 2020, Maneiro, in the insular state of Nueva Esparta.

A

rather colorful character, he also uses his media platforms to share some of his personal fascinations, especially, gastronomy.

Thus, on the

same page where photos of his company’s trucks, which collect garbage from the wealthiest municipalities of the capital, are displayed, he also provides tips on the perfect wine and

food pairings.

A lawyer by

profession, Elarba Haddad is a partner at the law firm Gadea, Lesseur & Asociados. The firm, founded more than 50 years ago, has among its members Gerardo

Blyde, a former deputy of the National Assembly, former mayor of Baruta, and founder of the Primero Justicia party.

At that

firm, Elarba also partners with his wife, Aitza Melo Castillo (“And the most important, I am Aitza’s husband,” he describes himself in his Twitter account profile as a footnote to listing his business positions, along with an image of the Virgin of

Valle), and with his stepdaughter, Mariana Flores Melo.

The businessman is also a part of the law firm Gadea, Lesseur & Asociados, where Gerardo Blyde, former mayor of Baruta and lawyer, is one of the partners. Photo: www.josesimonelarba.com

The businessman is also a part of the law firm Gadea, Lesseur & Asociados, where Gerardo Blyde, former mayor of Baruta and lawyer, is one of the partners. Photo: www.josesimonelarba.com

Flores

Melo is the wife of Henry Jesús Camino Muñoz, who is in turn one of Elarba’s partners at Fospuca, a company founded more than 30 years ago that Elarba acquired in 2014.

“I

found it interesting to get involved in that business with an interesting client portfolio. It was lacking some love for the business. In December

2014, I bought Fospuca Internacional,” he explains over the phone.

Money Leaves Traces, Cars Don’t

The

Bank of New York Mellon (BNY Mellon) was the institution that in 2015 presented to

FinCEN reports of 443 suspicious transfers totaling 66.5 million dollars. Among them, one connected to Venezuelan José

Simón Elarba.

Regarding

these transfers, two particularities provided the basis for them to appear suspicious to compliance officers at the bank who reported them to FinCEN. The first was that most transfers were conducted via nesting banking relationships, a financial term known in international banking jargon as downstream correspondents, summarizing the strategy in which a customer opens an account at large banks to facilitate transactions with smaller banks outside the principal bank’s country. Typically, these smaller entities are registered in offshore locations (with headquarters in tax havens, judging by common practices). In summary, the large bank “nests” the transactions of the smaller one at the account holder’s request, thereby making it their correspondent informally, not contracted.

Elarba indicates that the transfer recorded in the SAR corresponds to payment for legal fees. He stated that the client requested confidentiality and therefore would not discuss it for this report.

Elarba indicates that the transfer recorded in the SAR corresponds to payment for legal fees. He stated that the client requested confidentiality and therefore would not discuss it for this report.

The second

particularity referred to the presence, in the back and forth of the

transfers, of other creatures of the financial realm known as shell companies, entities that exist on paper only, with no physical presence. In the report to FinCEN, the reporting banking executives detail that such institutions “…can be created and used by individuals and companies for legitimate purposes. However, they are a concern for money laundering and economic crimes to operate and are structured in a way designed to cloak the details of transactions.”

Regarding Elarba, on Monday, July 14, 2014, one of those “large amounts of

dollars,” just over 1.48 million dollars, were transferred from two remittances from the South American International Bank Curaçao N.V., via the Bank of New York Mellon, to the account at the HSBC Private Bank (also highlighted in the FinCEN Files as one of the most negligent global banks regarding anti-money laundering measures) of José Simón

Elarba.

The

transfers originated from an account of a company registered under the name Parts and Accessories Supplier, Ltd. The details of the transfer mention a vague address for this company: Carleton Court. Nothing more.

A search across various databases yields no exact results of company names matching the one mentioned in the SAR. While there is an address known as Carleton Court in Barbados where several companies are registered, and there is one of similar name in its commercial registry, other data were found that would affirm it is the same Parts and Accessories Supplier. Barbados is recognized as a rather

secretive jurisdiction.

What is

verifiable, in any case, is that this non-transparent legal entity ordered the transfer of over a million dollars to José Simón

Elarba from that hermetic jurisdiction.

Fospuca provides services in several municipalities in the metropolitan area of Caracas, and in the states of Lara and Nueva Esparta.

Fospuca provides services in several municipalities in the metropolitan area of Caracas, and in the states of Lara and Nueva Esparta.

In a

first conversation with Armando.Info on December 1, 2020,

Elarba claimed he could not remember anything regarding these transfers. “I have no idea,” he asserted, although he recognized the following: “At that time, it was essential to do things through shell companies. There was a strict currency control, and all companies had to have entities outside the country to execute those transactions. Thank God and the Virgin, I conducted operations abroad; none were in the backyard here, in Venezuela. My accounts are in Switzerland and the United States, where I have my

money.”

However, in

a second communication three days later, he claimed to have contacted the owners of Parts and Accessories Suppliers, Ltd, the mysterious sender of funds in July 2014. “In 2013 we were hired by a transnational automotive company to organize their assets for sale, meaning, they wanted to be ready for possible sales, as indeed happened. The amounts of the two transfers are payment for fees for several lawyers and experts who participated in the operation. Finally, happily, the assets of that company, including its brand, were

sold.”

And the

origin and headquarters of the company? Elarba was emphatic in writing: “Before replying to you, I consulted the client and asked for permission to show the documents, and he requested that I maintain confidentiality on that. That is why I cannot give you more information.”

According to what

was stated in the SAR filed with FinCEN, this case exhibited several characteristics of a potentially irregular scheme: the “Bank of New York Mellon considers that the transfers reported here are suspicious because:

the transactions are conducted through a nested relationship involving the South American International Bank Curaçao, located in a high-risk jurisdiction; some of the parties could not be identified through public source research and therefore may be operating as shell entities; the source of the funds and their purposes cannot be identified; the transfers were sent to entities in high-risk jurisdictions [Switzerland, in Elarba’s case]; and there is a large amount of money involved.” Money for which FinCEN never received answers, if at all they were required.

Family Ties

Five

months after the sum of just over a million dollars reached José Simón Elarba Haddad’s Swiss account, he purchased Fospuca Internacional, C.A. Then, in June

2015, he registered Fospuca Servicios de Ciudad, C.A. And finally, in January 2016, Inversiones Fospuca Baruta, C.A. All these companies provided services to the Venezuelan state, according to the National Contractors Registry (RNC).

Elarba doesn’t waste any oppurtunity to promote his sybaritic devotion.

Elarba doesn’t waste any oppurtunity to promote his sybaritic devotion.

The

expansion of Elarba’s business has also become a point of family confluence. His wife is his partner not only in the law firm but also in Fospuca Baruta, Fospuca Servicios de Ciudad, and Fospuca

Internacional.

Family ties

also bind Henry Jesús Camino Muñoz, husband of Mariana Flores Melo (Elarba’s stepdaughter), in Fospuca Baruta, Fospuca Servicios de Ciudad, and Inversiones Fospuca Baruta C.A. Additionally, abroad, with Amancay Management

INC., a company with Panamanian records, where Elarba, Melo, and Camino serve as directors.

The

Camino-Flores marriage has also established its wealth away from blood relations. In May 2012, they registered a company named Hemaca INC with an official address on the commercial Alhambra street in Coral Gables. With this company, they acquired and registered a home on the exclusive Palm Island, Miami. Although the house remains in the name of Hemaca and, thus, in the name of the Camino-Flores, consulted sources claim that the couple has not returned since, as of 2017, when the

sanctions

imposed by the U.S. government on Venezuelan officials and state companies intensified.

You Fill It with Your Photos

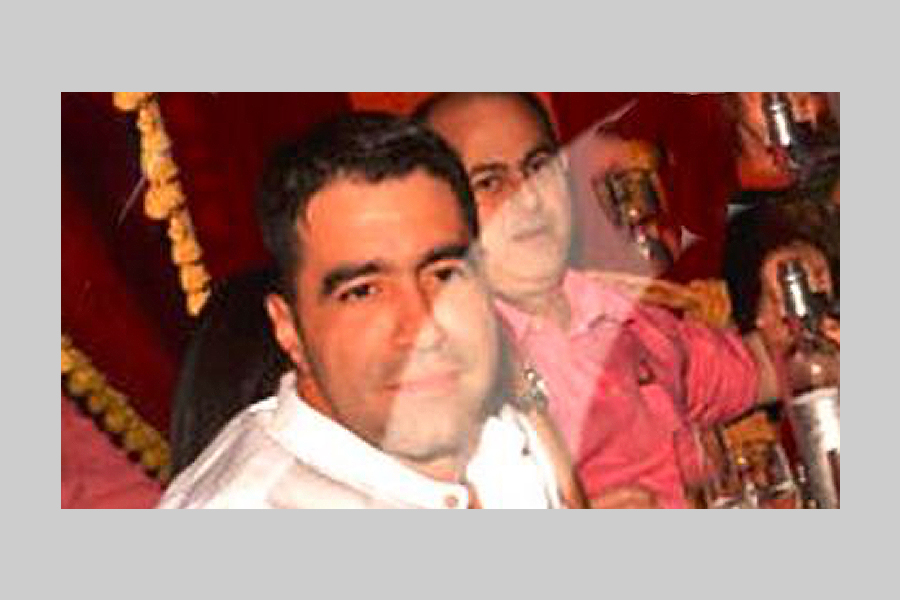

Both

Elarba Haddad and Camino Muñoz made headlines in 2015 for their connection with Carlos Erik Malpica

Flores,

known as Cilia Flores’ favorite nephew, who was treasurer of the Republic and managed Pdvsa’s finances. The link became evident through a photo of the three sharing drinks and laughter, which spread widely on social media.

Elarba

confirms the existence of the photograph. And his friendship with Malpica Flores

(who, he clarifies without being asked, is not related to his stepdaughter, even though they share surnames).

Elarba confirms that he is the one in the photo with Malpica Flores (Cilia Flores’ nephew). He claims that they met that day and started a friendship that persists today.

Elarba confirms that he is the one in the photo with Malpica Flores (Cilia Flores’ nephew). He claims that they met that day and started a friendship that persists today.

“That photo

exists, and I am in it. The friendship began the day of the photo. The story is very long and personal. It was back when I met Mr. Malpica,

who is my dear friend, my close friend,” he acknowledges.

Besides the

year of the million and the Fospuca purchase, 2014 was the year of the lawsuit filed by the number two of chavismo, Diosdado Cabello, against 21 directors of the newspapers El Nacional and Tal Cual from Caracas, and the web aggregator La Patilla. Elarba was among the board members of the first,

a traditional standard newspaper directed by Miguel Henrique

Otero.

The basis for

that defamation lawsuit was the reproduction in those media of a journalistic work originally published in the Spanish newspaper ABC, where

Leamsy Salazar, former bodyguard of Hugo Chávez and defector from the regime, linked Cabello to

drug trafficking.

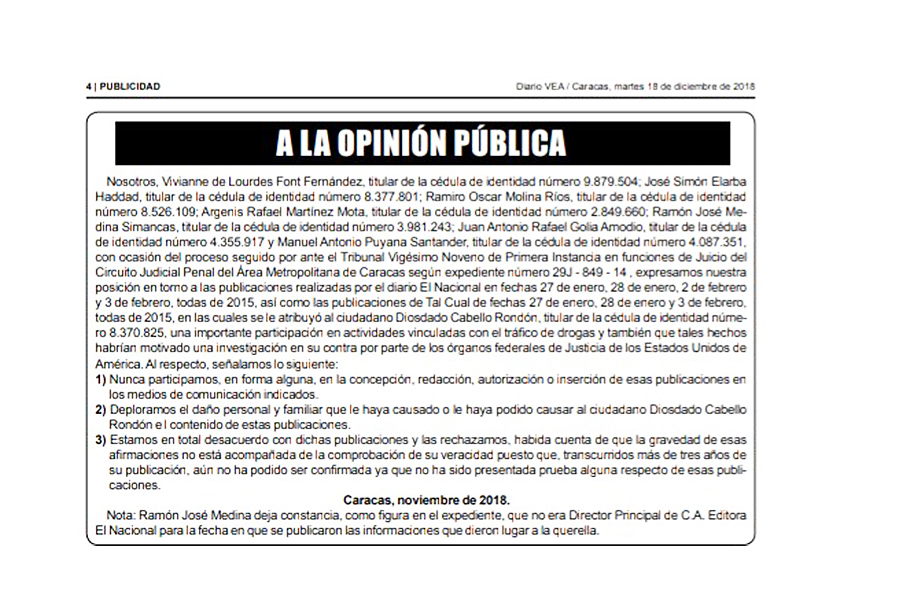

Elarba was one of the signatories of the statement in which a group of defendants retracted the publication about Diosdado Cabello.

Elarba was one of the signatories of the statement in which a group of defendants retracted the publication about Diosdado Cabello.

“As a result of

the lawsuit, all board directors were dissolved [N.de R.: refers to the board of the newspaper]. I tendered my resignation before the lawsuit. It was rather coincidental, but no one believed it was. What happened was that there came a time when my activity in Fospuca would produce a clash with my activity at El Nacional. It was delicate for someone serving as a director of El Nacional to also serve as a director of a public service… The direction of El Nacional was frontal, and I didn’t want to be in that situation because that was not my primary role. What I like is to work, manage my companies, and make money,” he details without remorse.

If Elarba’s relationship with Otero on the board of El Nacional was dissolved, the same was not true for a company based in Barbados. This is Iberonews

Limited,

owner of the website of the newspaper. The company records emerged in the so-called Paradise Papers, another leak handled by ICIJ in 2017.

Even today,

two years after the end of that trial, there are reports that maintain that, while other defendants (including the late Teodoro

Petkoff, founder of the Movimiento Al Socialismo party and Tal

Cual newspaper, former Cordiplan minister during Rafael Caldera’s second government, and former presidential candidate; the aforementioned Miguel Henrique Otero of El Nacional; and

Alberto Federico Ravell of La Patilla) were subject to restrictive measures like travel bans, Elarba received favorable treatment.

“How

did he achieve this? Through improper payments. How do we know this? Because the judges talk, and the clerks talk. It was learned that Elarba was given a change in the measure he had. Because of those payments. The other thing was the disgraceful manner in which he behaved in the trial hearing,” recalls Humberto

Mendoza D’ Paola, an attorney for Petkoff and Tal Cual, in an interview for this work.

“Mr.

Cabello: I regret everything about this. I have never said anything against you. If El Nacional said it, it’s because of Miguel Henrique Otero. I repeat this in front of everyone; I don’t believe what was said, and I apologize,” Elarba reportedly said during the trial hearing at the end of 2018.

But the

director of Fospuca refutes this today: “I had 18 months of a travel ban. When Cabello filed the lawsuit, I was in Istanbul

[the capital of Turkey]. That pact was signed by the majority of defendants. We reached an agreement with the complainant. We requested forgiveness,

Diosdado Cabello granted us forgiveness, and we went free. The agreement was to publish the notice three times in national press.”

And so it was:

Elarba was among the signatories of a statement that appeared in several newspapers, in which he and other defendants asserted they had not participated “in any way in the conception, writing, authorization, or insertion of those publications in the indicated media.” In the end, they added: “We disagree with those publications and reject them, given that the gravity of those assertions is not supported by verified truth.”

But if he managed to escape his ties with El Nacional in time, in recent years, he has been able to weave other friendships to maintain his media presence. For example, Elarba’s voice and face are regulars, explaining why urban cleaning service costs need to rise, on the screen of Globovisión, owned by the sanctioned Raúl Gorrín

Belisario.

Elarba has no issue saying he has been friends with Raúl Gorrín since 2009.

Elarba has no issue saying he has been friends with Raúl Gorrín since 2009.

“I know Raúl Gorrín, he is my friend. We have been friends since 2009. I have nothing to deal with that [the sanctions]. The one who has to deal with that is Raúl

Gorrín. What do I have to do with that movie? I emphasize the word: my friend Raúl

Gorrín continues to be my friend, and his situation with the Department [of the Treasury] is his situation. Any doubts, you have to ask him. What can I respond? That I can’t sleep at nights? The one who has to resolve is him,” he retorts.

Beyond

Fospuca’s relationship with the state, according to the National Public Contracting System, does he have a connection with Nicolás Maduro? Elarba insists several times that he does not. “None. To be precise, only cleaning through collaboration with the city of Caracas. But there are no contributions, contracts, or subsidies. In 2016, we acquired eleven high-quality trucks, and those procedures were carried out by Corpovex (…) but with Maduro, nothing. Absolutely

nothing,” they insist, coordinated voices and faces that in Raúl Gorrín’s Globovisión talk about, with carefree ease, recycling and pairing.