The secret

of Café Páramo is neither in its aroma nor in its flavor. In reality, it’s a name: Camilo Ibrahim Issa. He is a character and a face not widely known but is behind not only this expanding brand—packaging, marketing, and exporting coffee, and opening shops similar to Starbucks or Juan Valdez—but also one of the most spectacular business growths in the era of Chavismo, making waves through various simultaneous ventures in categories ranging from mass consumption to civil aviation.

Because yes: Camilo Ibrahim is also the man behind Plus Ultra, the nominally Spanish airline backed by Venezuelan investors that now makes headlines almost every day in Madrid’s newspapers. While the conventional wisdom suggests it does not matter whether the publicity is good or bad, the recent buzz around the airline’s name likely hasn’t been received well by Ibrahim, as it is linked to a scandal involving the apparently irregular allocation of 53 million euros in aid from the social-democratic government of President Pedro Sánchez. This has publicly placed the Lebanese-born businessman in the spotlight, despite his efforts to maintain a low profile, understanding the benefits of staying under the radar.

The uproar in Spanish media might suggest that this is Ibrahim’s primary business. However, that’s not the case. In fact, he oversees a broad corporate structure where Plus Ultra and Café Páramo are the most visible examples, but not necessarily the most ambitious or profitable. His organizational chart extends to other retail businesses, oil service firms, and even operations at the Maiquetía International Airport that serves Caracas.

Amid the depressed Venezuelan economy, filled with bad news, the recent boom of Café Páramo draws significant attention. It undoubtedly reflects a success story: its stores are popping up like mushrooms—even one in Canada—and the quality of the product is often praised by users on social media. However, not all aspects of this story are gourmet. For some reason, the company itself is intent on hiding the true owners, weaving a veil of darkness as intense as a good espresso.

Something slipped into Altamira

Grupo Páramo was born in the middle of 2016, when the economic crisis ignited by Nicolás Maduro’s government was undeniable. Two years later, the company surged into newspaper headlines and stirred social media controversy. In mid-2018, residents of Plaza Altamira in the Chacao municipality in northeastern Caracas opposed the establishment of a Páramo kiosk there, as rumors circulated that its owners were close to Maduro’s government. The company had arranged with Mayor Gustavo Duque to set up there in exchange for covering maintenance costs of the plaza. The agreement was symbolic: Plaza Altamira has represented the central bastion of anti-Chavista resistance several times, both at the municipal and national levels.

Amidst the controversy, and in an effort to manage the reputational crisis and the swirling rumors, the company then presented Guillermo Blanco Hernández as the mastermind behind the venture. The narrative he shared highlighted his banking background, claimed ownership, and denied any connections or favoritism from Chavismo. “We have no ties to the national government (…) We are entrepreneurs who believe in the country, we continue to bet on the country and work hard,” he stated during one of his appearances in October 2018.

While Blanco Hernández faced the media, the actual owner preferred to remain in the shadows. Camilo Ibrahim’s caution has good reasons. In an era when any substantial wealth can raise suspicions, Ibrahim, besides Páramo, has added several companies to his portfolio, such as Phoenix World Trade Inc, the firm managing the Zara brand and other companies from the Spanish group Inditex, and Pentech Ingenieros 05, a company with a long history of contracts with the state oil giant Pdvsa, according to the National Contractors Registry (RNC).

Many of these companies feature the same cast of collaborators and associates.

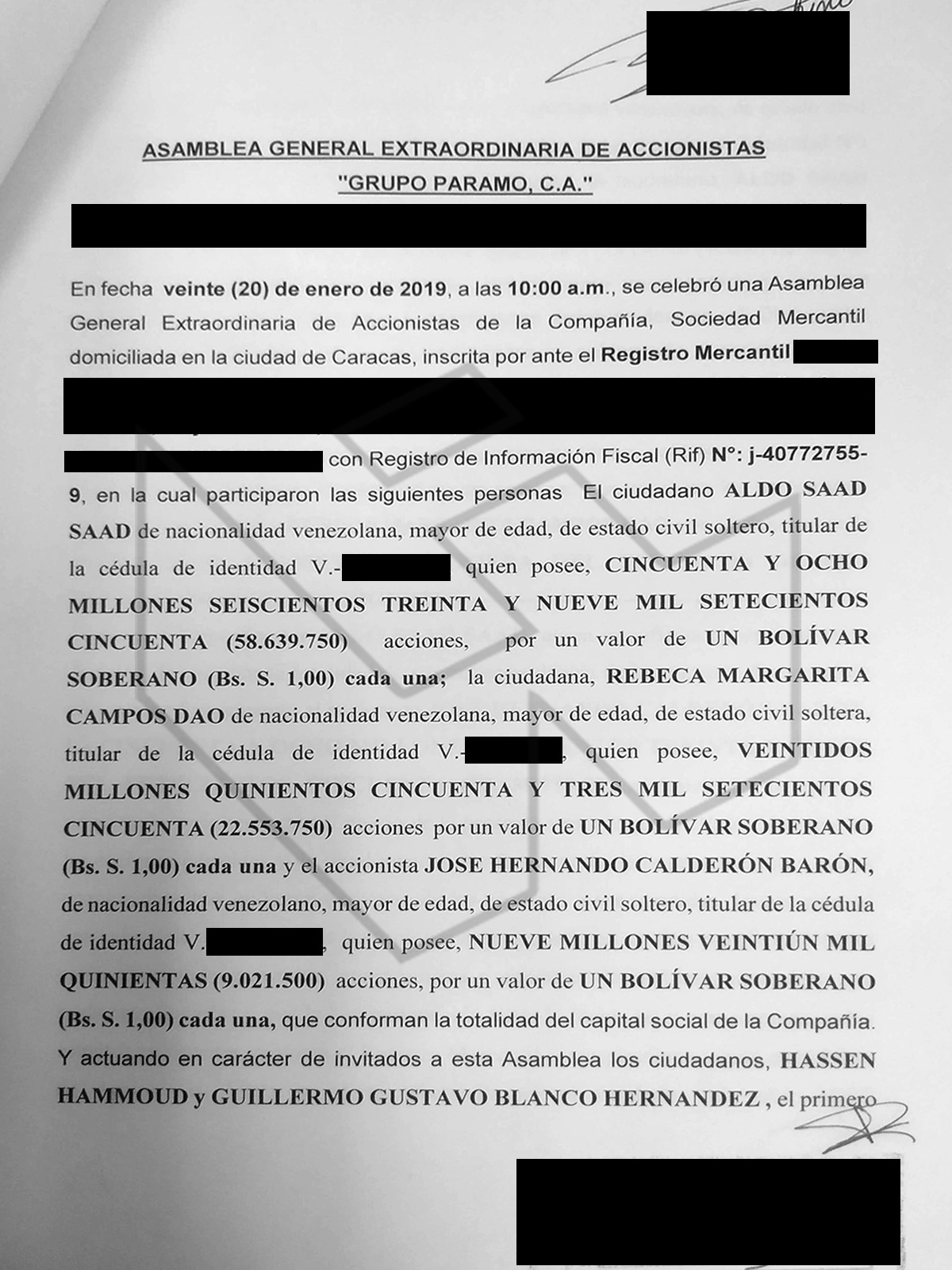

One such individual is Guillermo Blanco Hernández himself. Although he officially entered as a shareholder of Grupo Páramo just on January 20, 2019—only weeks after declaring himself the supposed founder of Café Páramo, as the commercial registry shows—he wasn’t alone that day; Hassen Hammoud, a Canadian national, and José Hernando Calderón Barón, who became a minority partner, also joined Páramo’s ownership.

In contrast, Kaled Osma Firas, a Brazilian national, and Aldo Saad Saad, a young Venezuelan lawyer, were the first partners since the company’s inception in 2016. Later, in October 2017, Youssef Hammoud and Ahmed Hammoud, both also Canadian citizens, became the legal representatives.

Both the Hammoud brothers and Aldo Saad Saad, the young lawyer, are recurring figures in Camilo Ibrahim Issa’s corporate structure.

For instance, Ahmed Hammoud shares a partnership with Hassan Ibrahim Osman, Camilo Ibrahim’s son, in Inversiones Planet Security, created in Caracas in 2009. They are also connected in Fire Bird Inc Limited and Check-In 18 C.A, through which they recently took control of some operations at Maiquetía International Airport.

In Caracas, Ahmed Hammoud, the legal representative of Grupo Páramo, is also a partner with Mohamed Ibrahim Ibrahim and Hassan Ibrahim Ibrahim, Camilo Ibrahim’s nephews, in PHX Security System. This company has a long list of contracts with the defunct state network Abastos Bicentenario, various ministries, the Presidential Office, the Bicentenario Bank, and even the Cuban Embassy in Venezuela. Their sales to these clients range from security cameras to holiday items, according to the RNC.

Not coincidentally, in its early days, Grupo Páramo shared the same address as PHX Security System: Quinta Serbal, in the Campo Claro urbanization in eastern Caracas.

But these are not the only connections between Grupo Páramo and Camilo Ibrahim.

Aldo Saad Saad, one of the founding partners of the coffee producer, is also part of Camilo Ibrahim’s holding in various duty-free and retail businesses at Maiquetía International Airport, as informed by sources familiar with those operations.

Many partner and representatives of Grupo Páramo are actually pieces in Camilo Ibrahim’s corporate structure.

Many partner and representatives of Grupo Páramo are actually pieces in Camilo Ibrahim’s corporate structure.

Camilo Ibrahim also serves as a director in Spain for Alimentos Los Páramos, registered last December, and La Compañía de Boconó y Biscucuy SL, created in January 2019. Both have been exposed recently, partly due to the crisis surrounding Plus Ultra. The names of both are not only linked with the Páramo brand but also with two coffee-producing regions in the Venezuelan Andes. Their objective is precisely to market “wholesale and retail of all types of food and especially of coffee in grain, ground, hulled, or in any other form, as well as the manufacture, handling, packaging, and roasting of all types of coffee.”

In these two young Spanish societies, Camilo Ibrahim shares a board with Raif El Arigie Harbie, Rodolfo José Reyes, and Roberto Roselli Mielli, all Venezuelans and also executives of Plus Ultra.

Grinding the competition

None of the reasonable impediments to setting up a coffee processing and marketing business in Venezuela have discouraged the frenzied expansion of Páramo. To be specific: neither the prolonged economic contraction, nor the collapse of national coffee production—which today does not exceed 350,000 quintals annually—nor the crisis of a sector affected for years by price controls and expropriations mandated by Hugo Chávez against various commercial roasters, some emblematic and historical, such as Café Madrid or Fama de América. Not even the small fuss surrounding the Altamira kiosk in 2018, which mostly spread through social media, had any impact.

In fact, all of these factors helped clear the market and favored Páramo’s emergence.

The company’s capital has continued to grow, its commercial offering includes at least four types of gourmet coffee, and shops styled after Starbucks or Juan Valdéz have been replicated in strategic locations like airports, cable cars, or even in the historic center of Caracas—something impossible to achieve these days without the national government’s approval.

Several Páramo outlets are even located in spaces where Chavismo once expropriated and ousted other entrepreneurs. This includes the store located at the Caracas cable car station in Maripérez, which had its concession taken from banker Nelson Mezerhane by Chávez, as well as the outlet at the old León de Oro hotel on Universidad Avenue, right in the center of Caracas—only two of the fourteen establishments they currently operate in the country. In 2018, it was Maduro himself who evicted small business owners of piñaterías and restaurants from this area near Plaza El Venezolano. Nowadays, Café Páramo’s location stands out amidst the chaos of Caracas’s historic center.

The León de Oro, which now houses Páramo, is a historical two-story building located between the corners of Sociedad and Traposos. Its image adorns many of the costumbrista chronicles of the city of Caracas of the Red Roofs. The building sports a white façade complemented by wide windows, a balcony, and wooden doors that rise high. Only a small circular sign with the brand’s logo interrupts a design reminiscent of the old urban grid of the city where Bolívar was born and lived. Nearby is also a location of Golfeados San Jacinto, another new franchise that, according to employees, is owned by “a certain Ahmed (Hammoud),” sharing the same name with the legal representative of Grupo Páramo.

When in October 2018, Guillermo Blanco, as the supposed owner of Grupo Páramo, wanted to deny the relationship with Chavismo, he asserted they got that space in the heart of Caracas by “submitting our little folder” with the project. “They told us to go ahead, under certain conditions, where we needed to improve everything regarding the image and façade of what was the old León hotel and with a lease agreement for a period.”

On August 12 last year, Guillermo Blanco participated in a virtual forum organized by the digital medium Analítica.com about “inspiring entrepreneurship stories,” but not as a representative of Páramo, rather for another emerging franchise of ice creams known as La Palettería. To not leave any hints out, the opener of the forum was none other than Camilo Ibrahim, in one of his few public appearances. Unconfirmed reports attribute the ownership of La Palettería to Ibrahim, which also has a location in another historically significant building in Caracas, the Los Andes building in Sabana Grande, on the ground floor of which Café Páramo is reportedly competing for space with the Chocolate Noble franchise, “from the same people,” as stated in a recent report from Armando.info. The Golfeados San Jacinto are also present there.

The emergence of Grupo Páramo in just five years has not gone unnoticed among old industrialists and coffee producers. Even before the surge of establishments or Café Páramo bags appearing in supermarkets, they had already heard of the company and its aroma.

“I’m going to mention two companies that are run by connected individuals, which are Café Páramo and Café Botalón—basically the ones ruling the coffee policy and prices today,” claimed Yoleidy Páez, a representative of coffee growers at a producers assembly with Juan Guaidó, in his capacity as president of the National Assembly, just days after proclaiming himself interim president of the Republic in February 2019.

If the true ownership is a taboo subject within the company, the same goes for the place where they process and package the coffee. Industry sources claim that Grupo Páramo was granted the Café Madrid plant in Guacara, Carabobo state, expropriated years ago by Chávez, under the figure of a comodato from the state-owned Corporación Venezolana del Café. “We left an oligopoly that at one time was held by Fama de América and Café Madrid, for an oligopoly of two companies plugged into the government,” asserts another coffee producer who prefers to remain anonymous.

Industrialists and coffee producers assert that Páramo’s coffee is processed and packaged in the roaster that once belonged to Café Madrid, which was expropriated by Hugo Chávez. Photo: @paramocafeoficial

Industrialists and coffee producers assert that Páramo’s coffee is processed and packaged in the roaster that once belonged to Café Madrid, which was expropriated by Hugo Chávez. Photo: @paramocafeoficial

The story of Grupo Páramo then represents further evidence of the policy, driven by Nicolás Maduro, of reprivatization or redistribution among allies of companies once expropriated by Chávez. “For years they destroyed the coffee business, and today it’s a venture of the plugged-in,” insists the producer.

Of course, none of this is in the company’s official narrative. For this report, neither Aldo Saad Saad nor Ahmed Hammoud responded to interview requests.

At the time of closing this edition, Reinaldo Gadea Pérez, Camilo Ibrahim’s lawyer, had also not replied to the questionnaire sent to his office via email. Gadea Pérez is a founding member of the firm Gadea, Lesseur & Asociados, which also includes Gerardo Blyde, a political leader and former mayor of Baruta, as well as José Simón Elarba, a businessman owning the waste collection company Fospuca.

It was Gadea Pérez himself, according to several sources, who attended parliament when deputy Freddy Superlano announced in 2018, then as president of the National Assembly’s Control Commission, an investigation against Camilo Ibrahim and other executives from his group for alleged corruption in contracts with the government for the sale of school supplies, as well as possible involvement in the business behind the Clap, the government program for distributing food and other subsidized essential goods.

“Mr. Camilo Ibrahim was sent a summons, but lawyer Reinaldo Gadea went instead. We quickly realized that Mr. Camilo Ibrahim had many supporters,” one interview source states. Documents obtained for this report confirm that Phoenix World Trade Inc, which manages Zara stores, signed contract number 0231 in 2015 with the state-run Corpovex for the sale of “school backpacks and pencil cases.”

Others cited by the National Assembly included Raif El Arigie Harbie and Rodolfo Reyes, who serve as executives of Plus Ultra in Spain and also share executive roles in the two companies established for the coffee business in Madrid. They too did not agree to the interview request for this report.

Just as Grupo Páramo dodged that storm in 2018, Camilo Ibrahim also escaped the noise arising from the summons by the National Assembly. Earlier, in 2013, he also evaded accusations related to the irregularities committed in the acquisition of foreign currency by several companies related to Phoenix World Trade Inc, which appeared to be part of the same structure by sharing executives and addresses but were individually applying for dollars from Cadivi, the office managing currency controls. By late 2015, a prosecutor from the Public Ministry requested the dismissal of the case against Phoenix World Trade Inc, which has since been restructured into a broader umbrella called Grupo Phoenix World Trade Inc, with companies in Venezuela, Panama, and the Dominican Republic, among other countries.

After all these storms and amidst the business boom he is leading, the circumstances allow Camilo Ibrahim to enjoy a cup of coffee and pontificate on the “new economic rebirth” of Venezuela, just as he did during that public appearance last year on behalf of Venezuelan entrepreneurs.