As soon as they opened the gate, a foul smell shot out. But the sight that emerged from within the enormous metal container was even more nauseating than the odor that preceded it.

Inside the container, around 28 tons of food purchased with public funds had spoiled over time due to the weather conditions in Puerto Cabello. Insects and rodents were fluttering around the food, “which were capable of affecting the quality of the product, both due to the direct damage caused when the insects feed, and the indirect damage caused by their feces, bodily secretions, and carcasses.”

This finding was described with forensic precision language in the investigation by the Public Ministry regarding the 2010 case, one of the clearest portraits of the corruption schemes of Chavismo in food imports, which, given the image of decay it displayed upon discovery, quickly earned the media and public’s nickname of the Pudreval case. An image that, only in that year 2010, was repeated in about 4,350 containers holding over 120,000 tons of food intended for the state-owned Venezuelan Food Producer and Distributor (Pdval).

The transformation of hundreds of millions of petrodollars into a collage of organic waste became one of the few state corruption scandals that had judicial repercussions under Chavismo. This performance did not take place, of course, in a non-existent museum of waste, but rather, as one would expect, in a state logistics depot. It occurred in a private warehouse.

At that time, the owners of private warehouses—among them, Braperca, owned by Isaac Sultán Cohén—were one of the few actors who profited immensely from the Pudreval scandal. How did they achieve this?

Interestingly, Pdval started as a nationalization experiment. One of many by the late President Hugo Chávez, which led to immense squandering of public resources. Launched in early 2008 as part of a supply plan to combat what the government claimed was a scheme of “hoarding and speculation” of food carried out by private entrepreneurs for political and economic purposes, Pdval amassed, by February 2010, funds of 2.2 billion dollars to achieve its objectives.

In practice, the purchasing transactions were made by Bariven, also a subsidiary of the state-owned Pdvsa, which was regularly in charge of buying supplies for the oil industry. But there, two incapacities came together: on one hand, Bariven had no experience in food purchasing; on the other, Pdval lacked the infrastructure or expertise to receive, store, and distribute the 1.7 million tons of food that the National Center for Food Balance (Cenbal) recommended importing as early as 2008. Cenbal was an agency attached to the Executive Vice Presidency of the Republic, headed at the time by Ramón Carrizález, a retired Army colonel and later two-time governor of the Apure state.

Amidst allegations of irregularities and corruption in the allocations, the Pdval initiative managed to import barely a third of what was indicated, or about 597,000 tons of food, which still exceeded Pdval’s distribution capacity by three times. This bottleneck ultimately led to thousands of tons of essential products, like rice, powdered milk, chicken, soybean oil, sugar, and beef, being stranded in ports, piled up in private warehouses subcontracted to deal with the situation.

Thus, an initiative created to bring the importation and distribution of food under state control to bypass the alleged sabotage of hoarders ended up benefiting private entities and generating an unwanted accumulation of excess in port warehouses.

One of the warehouses that benefited from these contracts was Braperca, the company of Isaac Sultán Cohén that, at that time, controlled a large part of the docks in Puerto Cabello and La Guaira, the two main ports in the country.

Now, Armando.info has gained access to two distinct leaks of documents that, when put together, allow us to establish that Sultán’s fortune—the money in his accounts, the number of his properties and works of art, as well as his business networks—experienced a sudden expansion just after the dealings of Pdval.

Sultán Cohén, repeatedly linked to Chavismo’s number two, Diosdado Cabello, and who emerged from nowhere as a significant player in foreign real estate and art markets, opened substantial bank accounts at Credit Suisse between 2009 and 2016—at least during the period covered by the analyzed data—ultimately becoming the Venezuelan client with the highest amount deposited in the now troubled Swiss bank, with at least 340 million Swiss francs—equivalent to around 360 million dollars at the time. At the same time he became a client of Credit Suisse, Sultán Cohén received payments from Pdval exceeding 50 million dollars for storage services.

The Beginning of the Pudreval Case

The timeline of Sultán Cohén’s business dealings has 2009 as a central axis. An official report from Pdval in June 2010 lists Braperca as the supplier that received the most payments in 2009, totaling 109.8 million bolívares (approximately 51 million dollars at the official exchange rate of that time). Among these suppliers appearing in the official document was also the Sahect Group, where Samark López, one of Chavismo’s preferred contractors, appears as a director. He was sanctioned in 2017 by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) of the U.S. Treasury Department for alleged money laundering.

However, 2009 would not be a positive year for Sultán Cohén and Braperca, at least seemingly. On March 24 of that year, Hugo Chávez decreed the creation of the state-run Bolivarian Ports (Bolipuertos), which resulted in the national government’s taking over the storage ports. Until then, regional authorities granted concessions to private warehouses to operate.

Braperca had been favored in Puerto Cabello by the former commander of the Navy, Carlos Aniasi Turchio, who was president of the Board of Directors of the Autonomous Institute of Puerto Cabello (Ipapc) and now operates and conducts business in the state of Florida, USA.

Just a month after Braperca was occupied by Bolipuertos employees in April 2009, Sultán opened the first account at Credit Suisse, through which at least 18.97 million Swiss francs flowed, equivalent to 20.1 million dollars. The account holder was also the Venezuelan Ángel Fidalgo de La Vega, a close partner of Sultán and who assumed the role of administrator for various companies of the mogul abroad.

This banking movement is verified in the leak that led to the Suisse Secrets series, a collaborative investigation coordinated by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, published in 2022 in which 163 journalists from 48 allied media outlets around the world participated, including Armando.info.

In June of that same year of apparent misfortune for Sultán, he continued sending his capital to Switzerland and opened another account at Credit Suisse, through which at least 94.93 million Swiss francs passed, equivalent to about 100 million dollars.

In October 2012, when the disintegration of Pudreval was already evident in the media, Sultán Cohén opened the account that would become the most lucrative at Credit Suisse, into which at least 233.3 million Swiss francs (or 247 million dollars) flowed by early 2016.

Not All Those Who Went Are Here

Another official document highlights Braperca’s prominence in the Pdval case. The final report from the General Comptroller of the Republic regarding the case, analyzing the program between 2008 and 2010, directly mentions the company. Among the irregularities found in this investigation is that both Bariven and the private warehouses maintained records that showed discrepancies in their figures. Discrepancies sometimes so significant as to amount to 1,000 tons per category.

For instance, Braperca ranked first in these inconsistencies by reporting 1,025 tons of powdered milk in its warehouses that, conversely, were not reflected in Bariven’s income sheets. The opposite also happened. Bariven recorded the receipt of 1,480 tons of meat, liquid milk, and chicken in the warehouses controlled by Sultán that were not in the inventories of the private company. According to the same report, this entire panorama revealed “the lack of coordination between Bariven and Pdval, which did not attend to a master purchasing plan.”

Ultimately, there were few criminal responsibilities regarding the Pudreval case. Only Luis Enrique Pulido López, former president of Pdval; Ronald José Flores Burguillo, and Mercedes Vileyka Betancourt Pacheco, two mid-ranking directors of the state company, were arrested and prosecuted. None of the other Board members, which included Egli Antonio Ramírez Coronado, Geroges Kabboul Abdenour, Ángel Ramón Núñez Hernández, and Jesús Enrique Luongo Demari, were charged in connection with the case. Years later, some faced trials for other accusations or appeared to be under investigation abroad.

Ramírez Coronado, uncle of then-Pdvsa president Rafael Ramírez—now in exile after Chavismo itself blamed him for leading a 1.35 billion dollar embezzlement of the state company—was accused of receiving bribes in the Odebrecht case when he led Pdvsa Agrícola, the company that was the primary shareholder of Pdval, in a scheme detailed by Armando.info.

The records of Braperca and other warehouse companies did not match those of Bariven, responsible for making food purchases for Pdval. Credit: Final report by the General Comptroller of the Republic.

Luongo Demari was arrested in 2018 for alleged irregularities in a fuel supply contract for the Paraguaná Refining Complex, of which he was manager before serving as Vice President of Refining at Pdvsa. He was later included by the Public Ministry headed by Tarek William Saab in the network of companies and individuals led by Diego Salazar Carreño, cousin of Rafael Ramírez, which is responsible for laundering over 2 billion dollars in the Private Bank of Andorra and whose members face criminal accusations in several jurisdictions.

Kabboul Abdenour, who was also president of Bariven, was accused of soliciting bribes in exchange for awarding or maintaining state contracts. In a lawsuit filed against Bariven in July 2009 in the District Court for the Southern District of Florida, USA, representatives of Validsa, Inc. accused Juan Carlos Chourio of demanding a bribe of two million dollars, on behalf of Kabboul, to keep an import contract for food worth over 160 million dollars alive. The agreement was part of the assignments made by Bariven intended for Pdval.

Records in the Cayman Islands

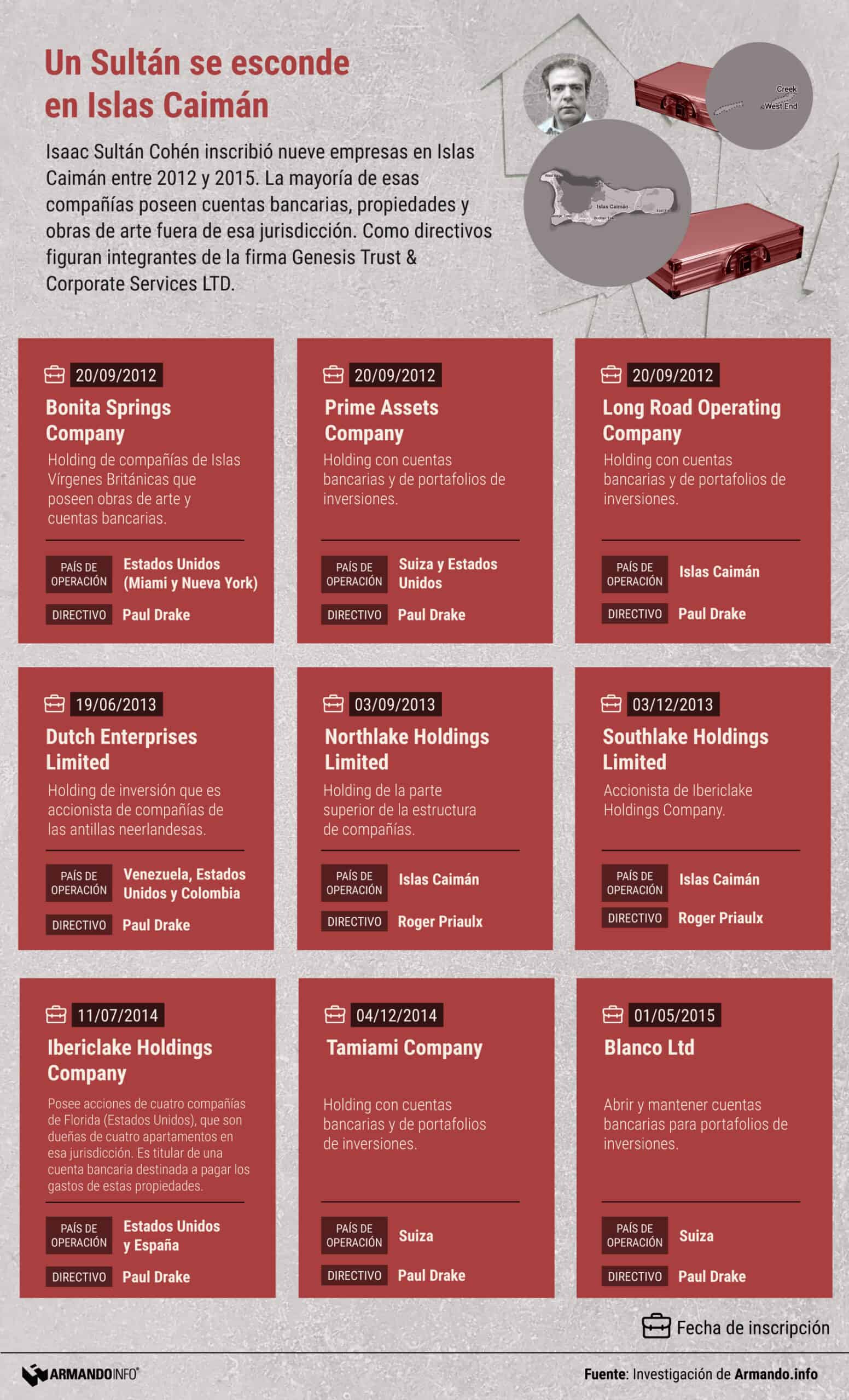

Armando.info also gained access to a set of documents from the corporate services firm Genesis Trust & Corporate Services LTD, based in the Cayman Islands, a well-known tax haven in the Caribbean, which provides further details about Sultán Cohén’s activities in the Swiss financial system. The leak shows that the Venezuelan entrepreneur opened nine offshore companies between 2012 and 2015, all based in this Caribbean jurisdiction, but mostly operating in Switzerland, Spain, the United States, Colombia, and Venezuela.

All the offshore companies registered in the Cayman Islands list a physical address in an office tower north of Miami Beach, which is also used by several of Sultán’s companies in the state of Florida. In 2012, Sultán began a voracious acquisition of properties and real estate that today sum to over 100 million dollars. Among these is the purchase of an entire building at 48 José Abascal Street in Madrid for 26.5 million euros on April 24, 2014. Here Sultán’s story once again intersects with that of former Deputy Minister Nervis Villalobos.

Sultán Cohén concealed his name through a Luxembourg-registered company called Fimis Holding S.à r.l., which owned the shares of a Spanish company named Basgaron Spain, the one that made the purchase of the building on José Abascal Street. To remodel the building, the Venezuelan decided to hire Elecnor and its subsidiary Área 3, a Basque multinational dedicated to the electric sector that had its first foreign subsidiary in Venezuela. During the years of Chavismo, it executed major projects amounting to billions of euros. Newspapers like El País in Spain linked the company to the payment of alleged bribes to Villalobos to obtain contracts in Venezuela and other countries.

By coincidence or not, in September 2017, Villalobos was one of Sultán Cohén’s clients, buying two luxury apartments in his recently renovated building, both valued at over six million euros. These properties were seized in 2018 by Spanish authorities for being acquired with funds from money laundering. Judicial investigations in that country accuse Villalobos of leading a network of money laundering that bought around 115 properties in Spain.

In 2020, a new investigation in Switzerland joined Villalobos, freezing 140 million francs in accounts of him and his children across eight banks in that country. “[There are] serious and concrete indications that the assets come from crimes committed abroad,” pointed out federal prosecutors in that country. The newspaper Tages Anzeiger, based in Zurich, covered the case, indicating that a luxurious apartment with a view of Lake St. Moritz was also seized, valued at six million Swiss francs. “The real estate market is a great gateway for money laundering in Switzerland. This case exemplifies that,” stated Martin Hilti, a representative of Transparency International Switzerland, to the media.

The documents accessed by Armando.info confirm that Sultán’s nine companies registered in the Cayman Islands remained active at least until September 2021. Among the companies operating in Switzerland are Prime Assets Company; Blanco Ltd., and Tamiami Company. All three have bank accounts or manage investment portfolio accounts.

Among the companies is also Ibericlake Holdings Limited, a company Sultán uses for his real estate investments. This offshore operates as a director of UPH01S LLC, a Florida-registered company that in February 2017 purchased a penthouse of 2,800 square meters, which includes its own swimming pool, for 25.5 million dollars. The property was the second most expensive apartment sold in Florida that year. Ángel Fidalgo, who shares an account at Credit Suisse with Sultán, later joined the board of the Florida company.

The Genesis Trust records add that Ibericlake holds shares in four companies in Florida and that each of these companies owns an apartment in Miami. “The company also owns a bank account used for covering the expenses of the apartments,” the document notes. Almost all the other Cayman Islands companies also own, in turn, shares of other companies that hold bank accounts or investment portfolios. These arrangements are often used to reduce tax burdens and conceal the name of the ultimate beneficiary of the companies.

Since February 28, Armando.info has sent requests for interviews, as well as a questionnaire, to the legal representatives of Sultán Cohén. The lawyers confirmed receipt of the questionnaire, but as of the publication date of this report, no responses had been provided to the questions. On March 6, a questionnaire was also sent to the corporate email of Genesis Trust, from which no response has been received.

With a History and No Traces

Among the nine companies, one registers a different purpose: Bonita Springs Company, registered in September 2012. The documents detail that it is a holding of British Virgin Islands companies, which in turn own bank accounts and works of art. It operates in the United States, specifically in Miami and New York City, where Sultán purchased over 50 million dollars in works of art between 2010 and 2015.

More than 27 million dollars of that amount went to Sotheby’s auction house. A British Virgin Islands company, Porsal Equities Ltd, was the one Sultán used to buy a significant part of his works from that auction house, starting in 2012. With his millions in Swiss accounts, the Venezuelan mogul has managed to obtain advice from financial and tax experts in that country, such as Thierry Sauvaire. According to sources knowledgeable about the transaction, Sauvaire participated in the scheme that allowed Sultán to purchase the building on José Abascal Street in Madrid in 2014 through Fimis Holding.

Currently, Sauvaire serves as the tax advisor to a French media mogul, Patrick Drahi, considered the eleventh richest man in France, media reports from that country indicate. In 2019, Drahi became the new owner of Sotheby’s, the auction house now being prosecuted in New York for tax evasion in a case involving Sultán.

Last November, the French newspaper Le Monde revealed that, in the same 2019, Drahi’s tax advisors devised a scheme for the French mogul to transfer his enormous collection of more than 200 works of art, valued at 750 million euros, to his children without paying taxes. The story stems from a series of documents stolen from Drahi by the cybercriminal group HIVE. The documents were published online after the businessman refused to pay the ransom demanded by the group. “Le Monde decided to use this data despite its criminal origin due to its public interest,” said the newspaper, citing experts who consider Drahi’s scheme as “an aggressive tax optimization, on the verge of legality.”

The strategy of Drahi’s advisors followed a tightening of tax regulations in Luxembourg that emerged after the scandal of the so-called Luxleaks, a massive leak of confidential documents from companies in Luxembourg in 2014. The documents reveal that one of the main advisors of the scheme was Sauvaire, who recommended that Drahi transfer ownership of his artwork from his companies in Luxembourg to shell companies registered in the names of his children in the Caribbean tax havens.

“This jurisdiction [St. Vincent and the Grenadines] was chosen because it was used to maintain the usual assets and liabilities of my previous employer, and we had accounts open in several banks without having ever had any issue of any type,” responded Sauvaire in an email to another advisor of Drahi.

Sultán used a similar scheme between 2012 and 2015 to purchase artworks from Sotheby’s. These acquisitions eventually led to legal troubles after he admitted to evading taxes on these transactions. However, he avoided trial by reaching an agreement with the New York Attorney General’s Office, paying 10.75 million dollars.

In 2018, Sultán Cohén paid 10.75 million dollars to avoid trial for tax evasion on art purchases totaling 27 million dollars at Sotheby’s. Credit: Ina Fassbender / AFP.

In 2018, Sultán Cohén paid 10.75 million dollars to avoid trial for tax evasion on art purchases totaling 27 million dollars at Sotheby’s. Credit: Ina Fassbender / AFP.

At the beginning of 2022, the digital outlet MaltaToday reported that a fiduciary company in that country was fined 12,500 euros by the Financial Intelligence Analysis Unit (FIAU), a government unit aimed at preventing money laundering. The agency found that the corporate services firm did not raise an alert of suspicious activities to the FIAU regarding Monrey Holding Ltd., a company of Sultán that used its services between 2017 and December 2020. Although it does not name them explicitly, the two articles quoted by the FIAU to consider that the firm had ample information to issue an alert about Sultán correspond to a Wall Street Journal article from November 2020 and a report by Armando.info in August 2021.

The Maltese fiduciary company, whose name is also not mentioned, acknowledged that it became aware of an adverse article regarding the former Pdval contractor in 2017, but that it was based only on allegations and that there was no new information related to the case. The company’s arguments may have some support from 2019, when Sultán had the dubious honor of leading another list of clients: that of the Spanish company Eliminalia, dedicated to reputation cleaning.

The mogul appeared in the top position among Venezuelans who contracted this company with payments totaling nearly 100,000 euros. Eliminalia provides services such as de-indexing links or creating fake news and web pages to bury undesirable information in search engines. “It’s not about eliminating things; it’s about making them unfindable. And this is a pleasing new definition of censorship,” explained Tord Lundström, technical director of Qurium, a non-profit organization based in Sweden that offers digital security services.

This is particularly useful for those wanting to erase evidence for judicial or journalistic investigations or to pass due diligence checks, like the one the Mediterranean country’s company had to conduct with its Venezuelan client.

Many of these profiles and “positive” news about the ship mogul no longer occupy the top positions in Google searches. However, a search for Sultán on social media still reveals a large number of false information. Despite his involvement in scandals such as Pudreval or the lawsuit against Sotheby’s, Sultán Cohén’s name remains relatively unknown both inside and outside Venezuela. The immense fortune of the Venezuelan mogul has also provided him with the means to remain almost unnoticed in the massive wave of corruption of the self-proclaimed Bolivarian revolution.