The name of Venezuelan lawyer Héctor Dáger is relatively unknown in his home country but is quite familiar in Swiss judicial circles and media reporting on the subject. The Federal Criminal Court (TPF) has rejected no less than ten appeals filed by Dáger and his shell companies. Since 2017, he has been under investigation for receiving $233 million, funds transferred to his accounts in Swiss banks by entities linked to the corruption scandal involving Brazilian multinational Odebrecht.

Three years later, in December 2019, the Federal Prosecutor’s Office (MPC) closed the proceedings against Dáger and returned $73 million that had been frozen during the investigation. Hasta entonces, Dáger had attempted to release the funds by filing requests with the TPF, but without success.

Finally, despite a previous opinion from the court stating that “the accounts attributable to Héctor Dáger were used for money laundering activities in Swiss territory,” federal prosecutor Annina Scherrer had to order the lifting of the fund’s restrictions on December 6, 2019, officially closing the investigation by finding that it had not produced evidence of illicit acts, and that authorities from Brazil and the U.S. were conducting inquiries into the same matters examined in Switzerland.

The investigations from Switzerland, Brazil, and the U.S. cover the financial operations conducted by Héctor Dáger between 2008 and 2016 in accounts opened in Switzerland, which received transfers of $233 million and €3.2 million from offshore companies linked to Odebrecht, as well as from the Venezuelan consortium OIV-Tocoma, in which the Brazilian group holds a 50% stake.

The Swiss federal prosecutor’s office could not identify evidence justifying an indictment, largely due to a lack of collaboration from Venezuela, which never responded to a letter requesting information sent to Caracas in February 2017.

Dáger, through his lawyers and shell companies, has pursued legal actions to prevent Switzerland from sharing with Brazil and the U.S. the documentation they requested as part of their ongoing investigations into the Odebrecht case. He argues that the authorities of those countries are not competent to prosecute the facts under investigation and claims that the Swiss resolution is equivalent to an acquittal, preventing further prosecution for the same matter.

On this point, Swiss justice has clearly indicated to Dáger that the abandonment of the procedure for lack of evidence “does not equate to an acquittal or dissolution excluding international assistance” and has made all disputed banking documents available to the requesting authorities.

Local press reports that all of his legal defense in Switzerland cost Dáger around 40,000 Swiss francs (approximately $43,000), which he paid to his lawyer Pierluigi Pasi, a former Swiss federal prosecutor. This amount represents only 0.02% of the deposits in Dáger’s accounts at eight banks: EFG Bank, Julius Bär, UBS, HSBC Switzerland, J Safra Sarasin, Credit Suisse, JP Morgan Switzerland, in Geneva, Zurich, and Lugano.

These amounts are merely “crumbs” compared to what Dáger reportedly received as a commission agent for Odebrecht. According to the company’s general manager in Venezuela, Euzenando Azevedo—convicted to 19 years in prison in Brazil—the Venezuelan lawyer charged a 2% fee on the amounts paid to the Brazilian multinational by the Chavista administration. Swiss prosecutors estimate this figure to be around $49 million located in various accounts.

The El Troudi Case

As confessed by the company executives and employees before the authorities in the U.S. and Brazil, the modus operandi of corruption maintained by Odebrecht over several decades involved paying bribes to high-ranking officials and politicians through intermediaries who opened accounts in their names and later transferred these accounts to the bribed parties. These financial operators were either associated with the Brazilian construction company or directly with the politicians and high officials involved. It is estimated that Odebrecht bribed over 1,000 individuals worldwide.

Dáger was not the only financial operator working for Odebrecht. Venezuelan Leopoldo José Briceño Punceles has been linked, based on testimonies from bankers in Antigua, to shell companies created by Odebrecht in Panama to channel irregular payments. Meanwhile, Luis Enrique Delgado Contreras appears as a beneficial owner of bank accounts related to several Venezuelan ministers, including Haiman El Troudi.

On July 14, 2017, Cuentas Claras Digital revealed that Swiss prosecutors had frozen several bank accounts belonging to Elita Del Valle Zacarías Díaz, the mother-in-law of former Minister of Land Transportation and Public Works and former president of El Metro Haiman El Troudi. The measure involved accounts in her name at Credit Suisse totaling $28 million, with additional accounts found at Banque Heritage for $4 million and BNP Paribas for $10 million. These accounts were initially opened by Luis Enrique Delgado Contreras, who also appears as an account holder along with Alejandra Urdaneta Tovar and Jorge Henrique Lander Siblisz, before being transferred to Zacarías Díaz’s name.

The Public Ministry led by Luisa Ortega Díaz cited Elita Del Valle Zacarías Díaz and María Eugenia Baptista Zacarías, mother-in-law and wife respectively of former Minister of Land Transportation and Public Works and former president of the Caracas Metro, Haiman El Troudi, as defendants. According to the documentation provided by the Swiss attorney general, Francesca Ghilardi, to the Venezuelan Prosecutor’s Office, “millions of Swiss francs that originated from Cresswell Overseas Ltd – one of the established fronts for Odebrecht – were transferred to the bank account of Alfa International S.A., which ended up in the accounts of Elita del Valle Zacarías Díaz and María Eugenia Baptista Zacarías in Switzerland and abroad.” Eventually, this sum could exceed $100 million, and is related to the Caracas Metro’s Line 5, the Guarenas-Guatire Metro, Line 2 of the Los Teques Metro, and the Petare Cable Car, all unfinished projects under El Troudi’s administration.

Despite the overwhelming evidence provided by the Swiss prosecutor’s office to Venezuela, Judge Luis Argenis Marcano Sarabia—in charge of the Eleventh Court of First Instance of Control of Caracas—exempted El Troudi’s wife and mother-in-law from any responsibility in 2018.

However, new documentation obtained by Cuentas Claras Digital reaffirms the payments made by Odebrecht to the company Alfa International S.A., with the final beneficiary reportedly being the mother-in-law of Haiman El Troudi, according to Swiss authorities.

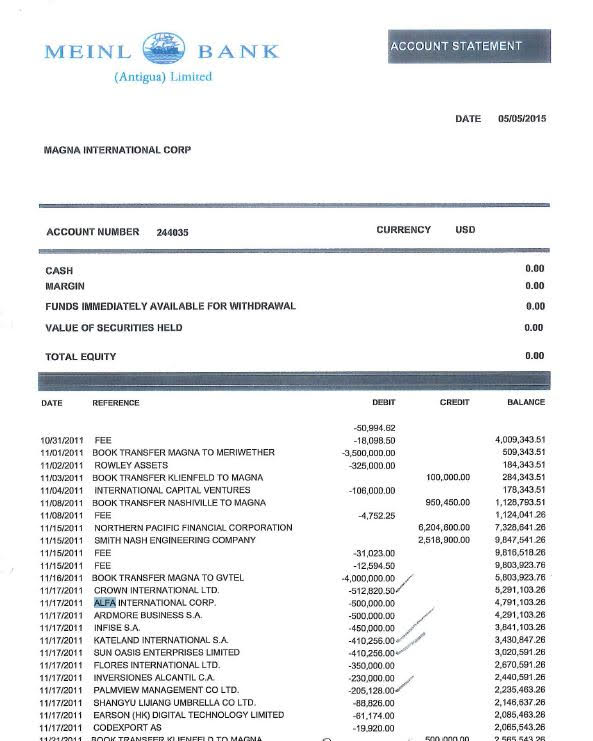

A withdrawal from account No. 244035 at Meinl Bank Antigua shows a transfer of $500,000 from Magna International Corp, one of Odebrecht’s shell companies, executed on November 17, 2011.

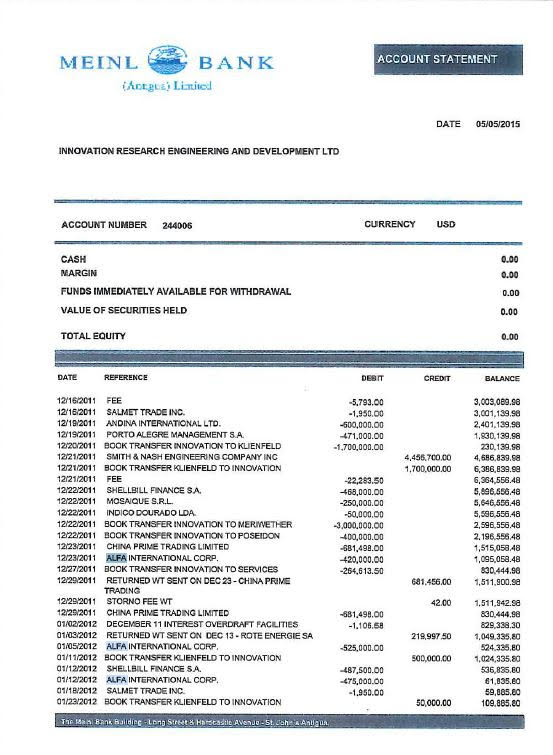

Additionally, through account No. 244006 at the same bank, another shell company of Odebrecht, Innovation Research Engineering and Development LTD, made three payments to El Troudi’s mother-in-law’s company, one for $420,000, another for $525,000, and a third deposit for $475,000, between December 2011 and January 2012.

Bank documents reveal transactions with other companies currently under investigation in the U.S. and Brazil.

Banks and Bribes

Meinl Bank Antigua Limited was acquired by Odebrecht in late 2010 when it was a small branch of an Austrian bank on the Caribbean island. Once they took majority ownership, it became the center of their corruption network: the bank of bribes.

Bank statements from Meinl Bank demonstrate another common modus operandi in such cases, similarly seen in the Banca Privada de Andorra scandal: numerous transactions under the label of book transfers conducted between accounts of various companies, simply transferring funds from one deposit account to another within the same bank, a mechanism used to evade money laundering prevention rules as an internal bank operation. Odebrecht employees have acknowledged in their statements before Brazilian justice that accounts were opened for companies whose initial holders were the intermediaries or frontmen of the bribed individuals, and were later transferred to the final beneficiaries.

The Secrets of Bambi

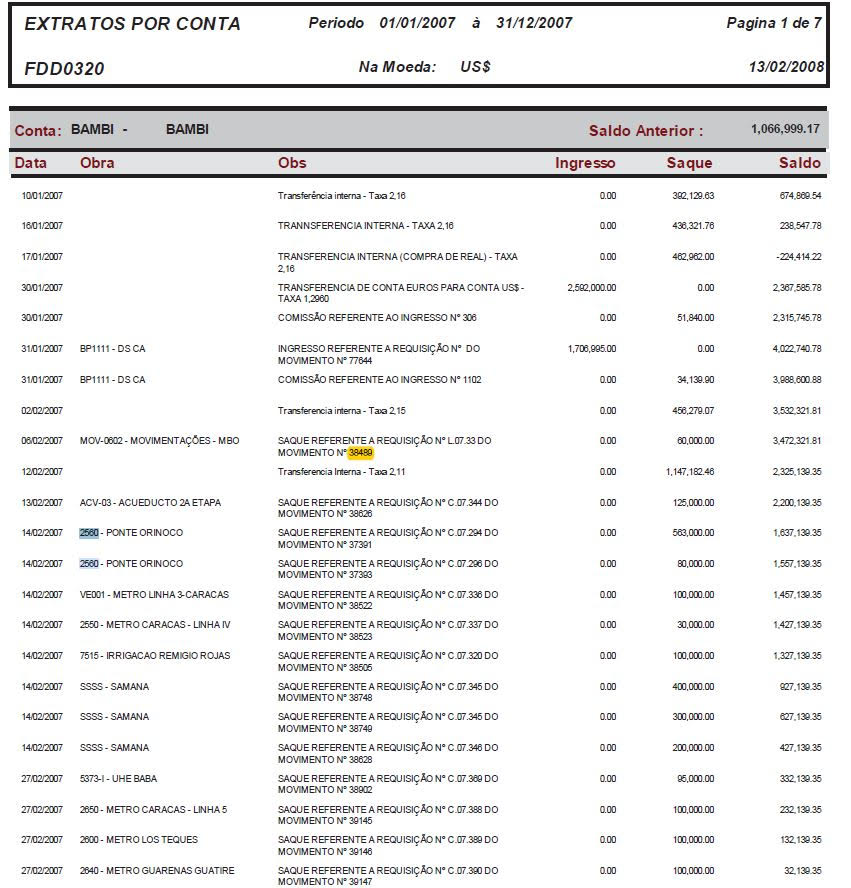

Cuentas Claras Digital also gained access to documents regarding Odebrecht’s payment system known as Bambi, which was directly controlled by Marcelo Odebrecht and the Structured Operations Sector, a euphemism for the slush fund used in the corruption scheme. This contains information about bribes paid in Peru, Argentina, Ecuador, Mexico, the Dominican Republic, and Brazil, as well as in Venezuela.

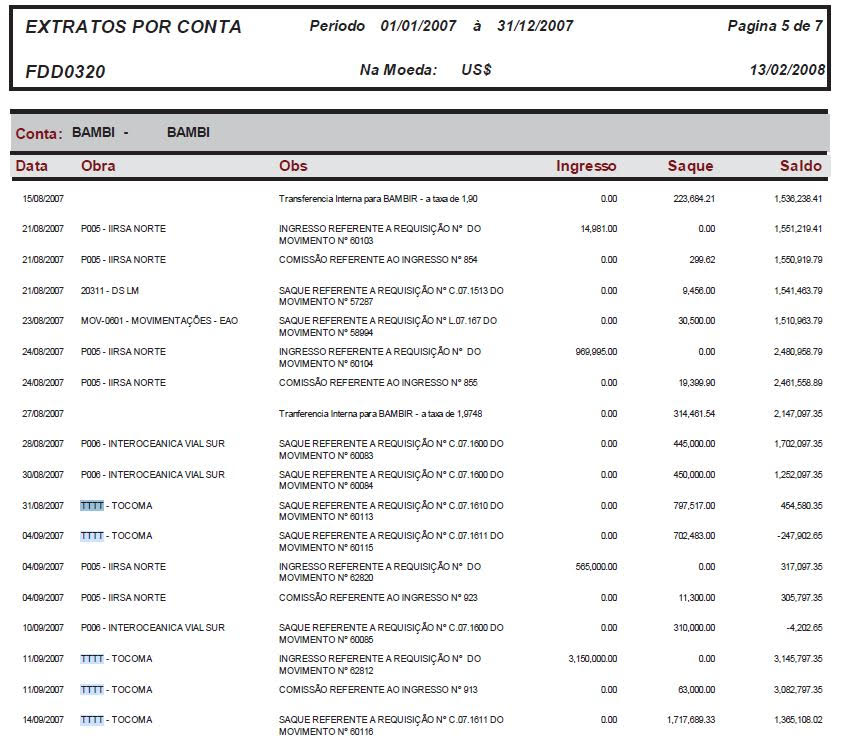

The copy seen by Cuentas Claras Digital outlines payments tied to the Tocoma hydroelectric plant project amounting to over $3 million in 2007.

Another form from the Bambi registry details withdrawals and commissions related to the Orinoco Bridge, Caracas Metro (Lines 3, 4, and 5), Los Teques Metro, and Guarenas-Guatire Metro projects, totaling over a million dollars.

Withdrawals have also been detected regarding bribes related to projects in the Dominican Republic (Samana Aqueduct), Panama (Remigio Rojas Irrigation System), and Ecuador (Baba Project), with works that remain either unfinished or problematic.

Recovering Venezuelans’ Money

Odebrecht reportedly paid $350 million in bribes to high-ranking officials in the Venezuelan regime, rather than the originally stated $98 million, as confirmed by Cuentas Claras Digital in September 2017.

A document from the U.S. Department of Justice released in December 2016 indicated that the Odebrecht Group paid $98 million in bribes to government officials in Venezuela between 2006 and 2015. This figure positioned Venezuela as the country receiving the highest amounts in bribes after Brazil.

Nine months after this announcement, international investigations revealed by Cuentas Claras Digital indicated that the actual figure reached $350 million, amount transferred by Odebrecht over nine years to accounts held by high-ranking officials of the Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro administrations.

International financial authorities involved in this investigation, regarded as the largest corruption case in history, have traced part of Odebrecht’s bribes to Venezuelan officials to banks in Antigua ($60 million), Curacao ($10 million), the U.S. ($15 million), Luxembourg ($25 million), Panama ($24 million), Portugal ($8 million), Switzerland ($150 million), Hong Kong, and other countries ($61 million).

Following the money linked to this corruption scandal in the case of Venezuela remains an outstanding task.

Odebrecht, Corruption, and Human Rights

The bribes from Odebrecht have led to imprisonment or prosecution and even suicide, as in the case of former Peruvian president Alan García, for several leaders in Latin America.

In Brazil, the origin of this international scandal, Odebrecht is part of a broader web of corruption involving the major companies in the country centered around the state giant Petrobras, which sparked the crisis that ousted Dilma Rousseff from the presidency and led to the imprisonment of her predecessor, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

In Venezuela, due to rampant impunity, the Supreme Tribunal of Justice in exile, after receiving the accusation from the attorney general against Nicolás Maduro and conducting the corresponding trial, sentenced him to 18 years in prison.

The nexus of political and economic corruption serves as a key to most human rights violations and criminal activities plaguing the countries. A clear example of this is the Odebrecht case and its impact on the democratic stability of our region.