Original de Juan Carlos Zapata

Teaser published in the July 1991 edition of Exceso Magazine. The full book is available here.

Unveiling. Skid. Money in hell. Pockets are torn and stitched again. The orgy of money. The boy who became rich sought his bodyguard. His suit costing 50,000 bolívares. An empty head. A stomach full of numbers. Of a lot of money. For sure, 1990 was the year of the fools. It’s called that because only fools lost or, in the best case, stopped winning in a steadily rising stock market.

The market rose all year. Speculative fever reached 40 degrees. Even mutual funds, which are investment instruments that maintain a conservative profile, obtained returns of over 100%. The one from Banco de Venezuela had profits of 130%.

There were those who among friends claimed to have gotten rich. Those who took advantage of the bus brought by the big sharks nearly burst their coffers. In any restaurant, when Orlando Castro’s name was mentioned—the speculator who launched the Public Offer to Acquire the Banco de Venezuela and raised the stock from 200 to 2,000 bolívares—the yuppies looked up, crossed themselves, and said: “Thank you God-Castro for making us rich.”

The casino in the center of Caracas

There are plenty of examples of young people who, at the beginning of 1990, held a portfolio of just a million bolívares, and by year-end were managing volumes of 10 million. The checkbooks from Banco Internacional served as proof, as it became the source of leverage for small and medium investors who only had to provide the shares they acquired as collateral, with stubs that once were checks, scribbles indicating transfers of five, six, and eight million bolívares.

“In whatever you invest, you win,” some brokers would say to those seeking information.

The kids saw the Caracas Stock Exchange as a genuine casino. They sold their brand-new cars and put all their money into stocks. No one lost. Everyone walked away with gains. Occasionally, they learned the lesson of settling for minimal profits. “I already won; let someone else win the rest,” says one of the market maxims.

Samuel Levy, “Samy” to his friends, entered the game a bit late, in mid-September. But he did so with the muscle of a weightlifter. He, who runs the exchange house Febres Parra, invested 60 million and, after two months, reported profits totaling 20 million. Without further thought, he acquired his own position on the stock exchange. Now he is a shareholder in Caracas’s trading floor.

However, Samy Levy, who bought shares in Banco Provincial at less than 400 bolívares, regrets having sold his position too soon, at prices just over 500. The stock rose to over 2,000, and Samy has told his friends he is sad because he could have made 200 million.

Orlando Castro, president of Grupo Latinoamericana de Seguros, made 3.5 billion by selling a strategic package of nearly 20% of Banco de Venezuela’s capital to José Alvarez Stelling, lord and master of Grupo Consolidado, for 7 billion.

The party of David Brillembourg

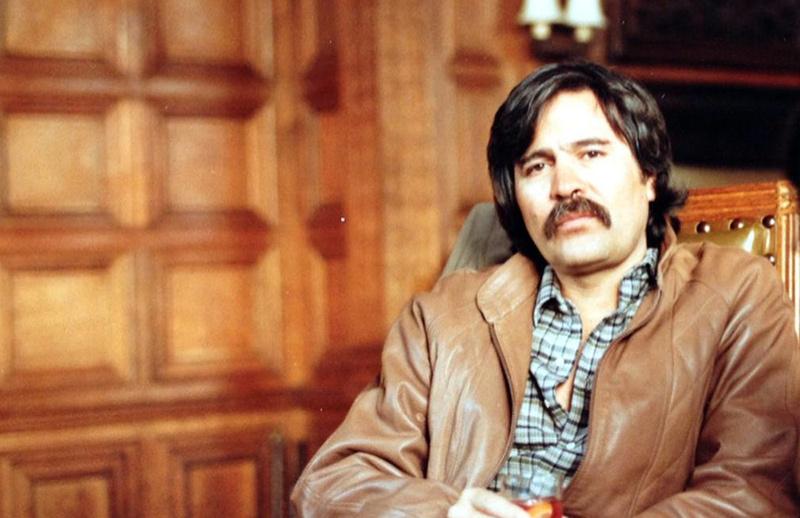

David Brillembourg – Courtesy of David Brillembourg

David Brillembourg, head of Grupo Confinanzas, who in late 1990 launched a bid against Cervecera Nacional and entered into conflict with Venezuela’s most powerful industrial and financial consortium, Grupo Polar-Banco Provincial, earned 500 million when he ultimately decided to relinquish the 50% he had acquired under an intelligent public relations campaign that often sounded like blackmail.

At the Confinanzas Christmas party held in the Grand Hall of the Caracas Hilton, even the union president representing the consortium’s employees approached Brillembourg and expressed pride in having a boss like him. That night, the White Label ensured everyone knew their place. Emotions ran high. No end-of-year company party was as touching as Confinanzas’. The employees could smell their employer’s money.

The Caracas Stock Exchange sold its new 12 positions for an average of 15 million bolívares, allowing it to purchase its own headquarters for 150 million. In 1989, trading operations amounted to just 12 million dollars. In 1990, the curve shattered the graph’s boundaries: 5 billion dollars.

Broker Gains

The leading brokers of the Caracas Stock Exchange, such as Rafael Alcántara, Víctor Flores, Juan Carlos Escotet, Juan Domingo Cordero, Alejandro Pulgar, earned over 300 million. This doesn’t include gains from their own portfolios, which likely doubled or even tripled that figure. Escotet, who executed the takeover against Banco de Venezuela, made over 600 million. Flores, who intervened, contracted by David Brillembourg, in the Cervecera Nacional bid and in the acquisitions of Mantex, Banco Unión, Banco Provincial, and Banco Hipotecario de Crédito Urbano, earned around 500 million.

The Maraven Savings Fund, a subsidiary of the state-owned Petróleos de Venezuela, caught the fever. It developed its own portfolio, consisting of almost 40% in loans to high-ranking companies; 15% in bank placements; 9% in real estate; 4% in partnerships with other firms; and 34% in stocks, bonds, and securities.

The fund gained credibility when it purchased 8 million shares of Vencemos, the cement corporation of Grupo Mendoza, from Banco de Venezuela, which was besieged by the war declared by Grupo Latinoamericana de Seguros. The shares were acquired in August for over 1.1 billion bolívares, at an average of 150 bolívares. It later sold six million of the stock to Chemikal Bank and Banco Provincial in a deal executed in New York, at an average of 200 bolívares. The profits totaled 500 million. Even better, as the fund bought on credit, it sold for cash.

The institution reported returns of over 100% to the company’s employees. Each of them wanted more money deducted from their paychecks to continue operations. But doubts arose from the headquarters, accusing the fund administrators of not acting transparently. Carlos Castillo, president of Maraven, had to retire to avoid resigning because he had endorsed transactions that were later investigated. The fund’s stars, managers José Petit and Bartolomé Ruggiero, had to close up shop and flee abroad.

The Culture of Money

The culture of money has arrived when everything seemed lost. The youth who have displayed imagination and skill in making quick and even easy profits are precisely the same who grew up hearing a single word from their parents: “crisis.”

But they also heard that crises bring changes. They merely embraced them. By the way, after a year when the Venezuelan economy hit rock bottom, with an impressive drop in GDP, high inflation and unemployment rates, and with international reserves almost at zero, not to mention the disastrous burden of external debt. For God’s sake.

The theory of big stock players teaches that in times of economic depression, the market explodes. That’s what happened in Venezuela in 1990. Otherwise, the two bids and the many corporate hunts that unfolded over just a few months wouldn’t make sense.

The physical environment of the Caracas Stock Exchange was bursting. Everyone wanted to witness the trading. It wasn’t Wall Street, but it was a novel spectacle where, like a scene from a movie, a nicely dressed boy with stylish haircuts and rosy cheeks might burst into a run because he had just earned half a million bolívares. The air conditioners had to be reinforced with wall fans. The auctioneer was sweating more than usual. Brokers could not communicate face-to-face with their clients at the auction. They were forced to follow their brokers’ advice: buy yourself a cellphone.

This initiated the cellphone syndrome; Cantv, the state telephone company of Venezuela, couldn’t cope with the demand. Lines were provided, but communications became impossible. In the auction, clients and brokers opted to learn from the Japanese, and hand signals, arm gestures, and winks became the norm. Alternative communication, a sociology professor from any school of social communication might have said. The cellphone was merely status, the university professor would add, likely continuing with his pre-Gorbachev ideas.

100 Million in a Year

Money flowed. César Alcántara, a newly graduated economist, started in 1987 with 40,000 bolívares. Profits in 1988 and 1989 were modest. In 1990, however, he dared to manage other people’s portfolios. He borrowed from banks and moved over 100 million. His profits totaled 20 million bolívares.

Now, 70% of his money is invested in the real estate market, which he believes will be the sweet spot this year, as the stock exchange was in 1990. Or take Andrés Ponte, a civil engineer who fell from grace when the construction industry collapsed. He salvaged a million and began actively trading on the stock exchange. He is one of the few investors who maintains technical and fundamental analysis records of companies. The fact is Ponte has an investment portfolio worth no less than 100 million bolívares.

Meanwhile, Jesús Tadeo Prato was an apprentice at the National Securities Commission while graduating as a lawyer. His uncle, Enrique Urdaneta Fontiveros, scolded him for investing in the stock market. In part because Urdaneta Fontiveros was the president of the Commission and had to safeguard its image. Jesús Tadeo Prato moved to Banco Mercantil. By then he had graduated and from the Torre de David saw the market up close, from a financial center. He began operations with 20,000 bolívares and in 1990 earned 10 million. He became independent and currently is a lawyer for several brokers.

They are classic examples of small investors who invested, persisted, and profited. For them, it was about becoming rich. They never dreamed of such wealth. They believe that life has just begun.

Others, small investors, came and went. They arrived with no information and left scared by some ill-intentioned brokers who spread negative rumors, claiming they would ruin the yuppies. In their flight, some stocks dropped, though not significantly, and most of the losers were scared and uninformed small investors.

In contrast, those who speculated heavily, as they were high-ranking executives from companies and banks, withstood the few blows and actually benefited as they bought low during the fearful race and sold high.

Orgies in a 5-star hotel

Next, they were seen desperately spending the easy money they had won. Some bought properties. Others went to Caribbean casinos to gamble up to 3,000 dollars in a weekend. Samuel Levy was in Puerto Rico, César Alcántara in the Bahamas, and Carlos Acosta, a protégé of Grupo Confinanzas, in Aruba. A few could afford to buy their own Jet Commander twin-engine aircraft or their 300,000 dollar boat. They left La Carlota airport every Saturday morning bound for Los Roques, with their holds overflowing with imported whiskey, vodka, and gin.

Some rented consecutively—the weekends, of course—the presidential suite of a 5-star hotel in Caracas, where they organized wild orgies. They would call a phone number in the upscale Los Palos Grandes neighborhood and request girls aged between 18 and 20 years. Generally, it was six for six. Among them was a broker who handled the positions and arrangements. Each weekend’s bill was no less than half a million bolívares. There were baths in champagne and whiskey and other additives.

The Happy Awakening of Víctor Gill

On Monday, May 27, Víctor Gill woke up happy. With a smile from ear to ear. With his right foot forward. With a yawn that nearly swallowed his feather pillow. And with a stretch that almost hit his wife. The president of Bancentro signed an exchange of shares with Banco Latino. He granted Pedro Tinoco’s institute the 11% of the capital he held in Banco de Maracaibo, in exchange for several million bolívares and 85% of the shares of Banco Hipotecario Oriental.

This operation completed the integration of the Bancentro financial group, which began operations over two years ago with an insurance company and a leasing firm. The latter was negotiated with Grupo Cordillera. However, he retained the name. Then came the acquisition of Banco Financiero, owned by Beto Finol, which is now called Bancentro. The latest development has been the establishment of the Brokerage House, where profits in 1990 rounded up to 100 million bolívares.

This is not the first time Victor Gill has closed a deal with Latino, as he previously sold his 20% stake in Banco Capital for over 150 million bolívares. Gill also sold to his namesake Víctor Vargas the 30% of Banco Barinas, which was later acquired by Latino itself. In other words, it’s a whole web of interests.

This banker, who prefers addition and multiplication—enemies are not divided; they are avoided—has always believed that buying Banco Financiero was a smart move. He acknowledges that the institute was strong because it managed to weather the storms of crisis. It didn’t disappear. He and his partners injected fresh resources and immediately increased the capital to 300 million bolívares. Later, they changed the name to Bancentro, although for a long time stationery and agency signs still referred to it as Banco Financiero.

Negotiations with Banco Hipotecario Oriental took place directly with Gustavo Gómez López, the “number one” of Banco Latino. These have been smooth and friendly negotiations, as Gill’s custom is to close deals where neither party feels deceived. He also believes that “when negotiating with an intelligent person, rational decisions are made.”

With this transaction, Bancentro penetrates the eastern region, where it has been glaringly absent. Banco Hipotecario Oriental operates three points in the area. This union gives them total control over deposits of 14 billion bolívares. They now feel a bit more than medium-sized. As such, they note that in competition with the big players, they have the advantage of speed and agility in decision-making. They have learned from their former partner David Brillembourg that “the tiger eats quickly.” Nevertheless, he states that “my measure isn’t bank rankings but the fulfillment of strategies and sales.” Their target is personalized banking, serving personal companies managed and operated by their owners.

Víctor Gill has arrived at Bancentro to stay. This time, things won’t unfold as they did with his alliances at other banks, where he left due to his “money-driven” nature. Now he has said he feels like a full-time banker, alongside partners like Carlos Gill, his brother, Omar Pernía, and Omar Camero.

They have negotiated the current headquarters in El Rosal, located in the golden mile, with Grupo Latinoamericana de Seguros, and are nearing completion of a brick tower with green glass in front, which has turned out to be a 500 million bolívares investment by the partners. By chance, and without planning, they are located in the heart of what will become Venezuela’s financial center. The relocation of the Caracas Stock Exchange to El Rosal has turned the area into a small City.

The World of Casablanca

Carlos Dorado is also a success story, albeit of a different kind. Jumping from the El Cementerio neighborhood to the heights of wealth isn’t an easy climb, for Carlos Dorado’s first step after graduating as an economist at Andres Bello Catholic University was to hit the streets looking for clients. In that pursuit, he reached Grupo Italcambio, where he met the owner’s daughter, Gabriela Pizzorni. The world turned, and he ended up marrying her.

This way, he is embedded there and part of the class of successful youth flaunting wealth on their faces. He does so more in a jacket or suit, as that’s precisely what his latest business is about. The key point is that he has become part of the group, even standing out because most yuppies barely know who Bertrand Russell is; Carlos Dorado is, after all, passionate about philosophy. That’s why he says he belongs to the distinctive class of money.

He is also the proud owner of a trendy store—business he founded with 40 million bolívares, which he says came from his own pocket. A store showcasing the most exquisite inventory of designer Adolfo Domínguez, where money players come to settle bills of 400,000 bolívares. Interestingly, prices in Casablanca range from 18,000 to 48,000. Just months after opening, the client list numbered 300, and monthly earnings hit 2 million bolívares. With clients like this, obviously. Dorado was born in Forxa, a tiny village of 100 people in northern Spain. He came to Venezuela at age 10. His father was a messenger, and his mother a school cook. He admires more the grocer, the butcher, or the bakery owner than his speculator friends. His profile leans toward creating enduring businesses. He’s someone who works 15 hours a day. However, one of his greatest achievements is mastering how to navigate society like a fish in water. A golden fish.

The culture of money dictates displaying what one possesses. John Taylor, in the book The Circus of Ambition, writes: “When an individual’s wealth reaches a certain level, it becomes impossible to visibly consume enough to showcase the extent of that wealth. Hence, they must resort to vicarious consumption or delegated consumption. Others will consume on their behalf.”

In this world of illusions, of appearances, of wanting to display not who one is but what one has, a Porsche, a Ferrari, a Bulgari jewel, a Lear Jet, a ski season in Gstaad, and—of course—a good “rag,” as Carlos Dorado daringly calls clothing, are needed. Dorado claims he outfits money. He has interpreted the rebellion and elitism of those participating in the money orgy. The daring, the audacity, the risk, the high-stakes game. “In short,” Dorado says, “the bodies of the winners cannot be clad in a Clement, a Vogue, or an Ottaviani; they need something more avant-garde, more elite, and wearing it must require not just money, but a taste for the exclusive… and even a good physique.”

Casablanca, like the original film, has its protagonists, including Dorado himself. Adolfo Domínguez is among the world’s top five designers and Carlos Dorado’s partner in this venture. It all began with a slogan: “Wrinkles are beautiful.” Today he is hailed by the global press as “the designer of the Immense Minority.”

Adolfo is elite: a philosopher, a vegetarian, a writer; he has already built a legendary name in fashion by age 40. His clothes are worn by those, Dorado says, “who, having achieved everything, desire simplicity and manage to stand out with it. Paris is his home, Japan his stage, and Caracas his weakness.”

Gabriella Pizzorni, Carlos Dorado’s wife, is the daughter of Mario Pizzorni, founder of Italo Bank. She inherited from her Milanese roots a keen taste for design; from her mother, class; from her father, hard work; from her sculptor uncle Pizzo, forms; and from Italcambio, the factory that meets the desires of those wishing to signal to the world that distinction stems from wealth and spreads everywhere.

Casablanca is a contrast in the land of contrasts: luxury and hunger, wealth and misery… money and the devil. Who will be who? Carlos Dorado leaves the questions open: simplist? philosopher? new rich with a poor mindset? snob? While they figure it out, he, among other things, says he dresses money.

According to Dorado, “All those I’ve known who are vain are fools, and all fools are vain; and very few realize that ‘dust you are, and to dust you shall return.’