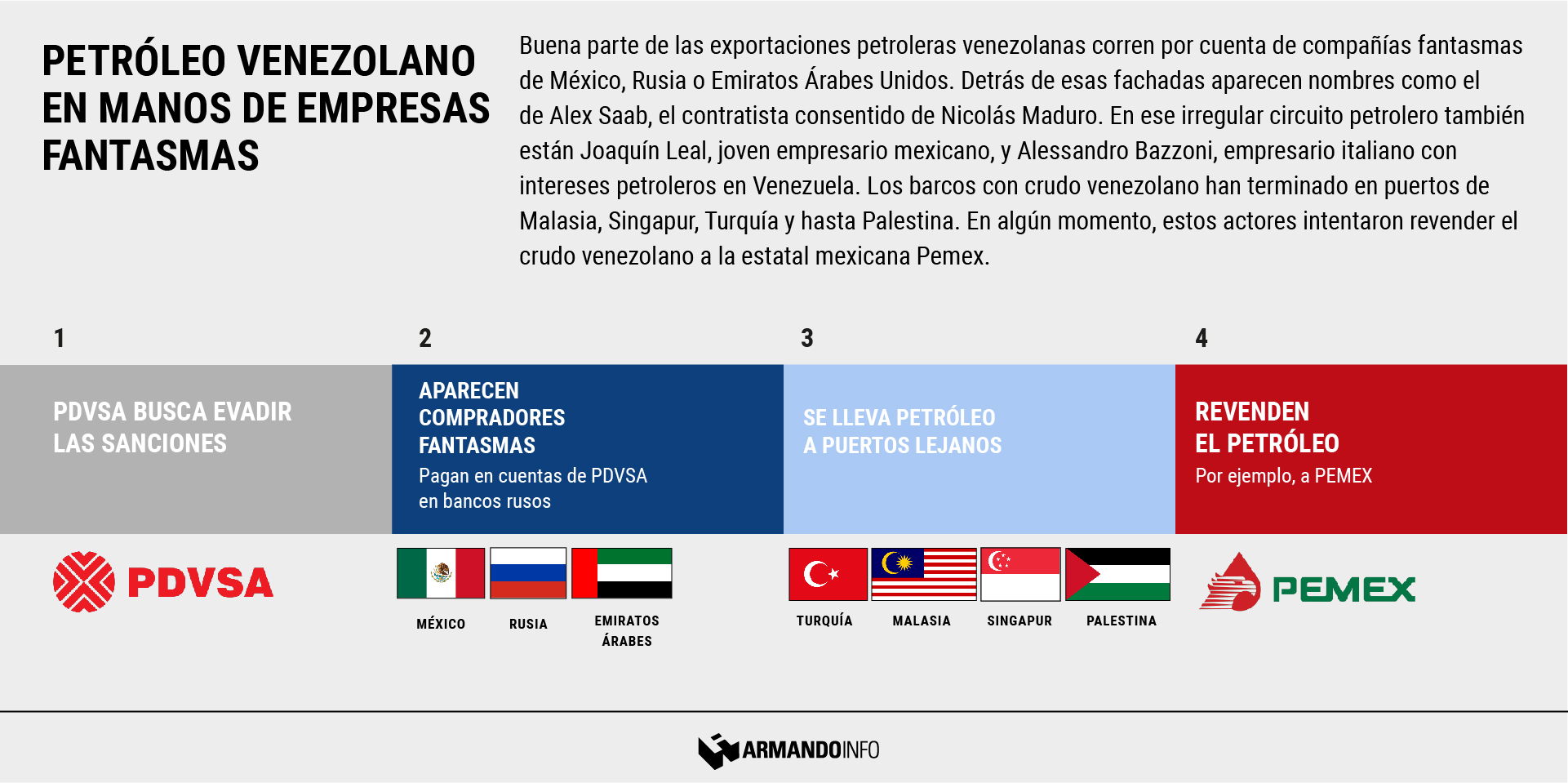

Contrary to popular belief, the arrest of Alex Saab Morán seven months ago in Cabo Verde and the nearly simultaneous sanction by the U.S. Department of the Treasury against the Mexican company Libre Abordo, linked to Saab and which had been trading part of the crude produced by Venezuela since mid-2019 under a supposed “humanitarian exchange,” did not disrupt the clandestine circuit of Venezuelan oil exports designed to evade sanctions imposed by Washington against the state-owned Pdvsa in early 2019.

New documentation obtained and reviewed jointly by Armando.info and the newspaper El País confirms that, in reality, the names of Saab and Libre Abordo represented just the tip of the iceberg in this scheme. Connected to both were a sophisticated network, under the command of Saab and entrepreneurs Joaquín Leal—a Mexican—and Alessandro Bazzoni—an Italian—who traded millions of barrels of Pdvsa crude at millionaire prices in euros through shell companies registered in jurisdictions like Mexico, Russia, or the United Arab Emirates.

The name of Leal, just 28 years old, had already surfaced in mid-2020 with the revelations about the framework built in Mexico with Libre Abordo and Schlager Business Group, both of which were subjected to U.S. sanctions.

Bazzoni is also not a stranger. As the head of the trading company Swissoil Trading S.A., he is involved in Elemento Ltd, a partner company of Pdvsa in the mixed enterprise Petrodelta for exploiting fields in the Orinoco oil belt. This business web, which also included the late Oswaldo Cisneros, was exposed by the 2017 leak of the Paradise Papers. But it is only now that the importance of Bazzoni in the multimillion-dollar operation is clearly confirmed, as he, along with Saab and Leal, created a virtual parallel marketing department in informal outsourcing for Pdvsa.

Last June, the U.S. Department of the Treasury identified Joaquín Leal alongside Alex Saab as key players in a scheme to evade sanctions against Pdvsa.

Turkey, Malaysia, Singapore, and even territories managed by the Palestinian National Authority were among the often-exotic destinations for oil shipments managed by this network.

The documents also reveal that these same actors first attempted to resell Venezuelan oil to Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) and then forged documents to purchase gasoline and heavy fuel oil from the Mexican state-owned company, used for ships and electricity generation.

It is also clear that, in their effort to dodge sanctions and international oversight, Pdvsa and its intermediaries are reproducing approaches previously used successfully for acquiring and importing supplies for the Local Supply and Production Committees (Clap). Not in vain, it was from Mexico that Saab and his first partner, fellow Colombian Álvaro Pulido Vargas, began to extend their commercial empire, fueled by the petrodollars from Nicolás Maduro’s government.

From Russia with love

As verified in papers obtained by Armando.info and El País, on August 11, 2020, an email arrived at the “contract administration” department of Pdvsa. From a user with a Russian domain (.ru), a “statement of account as of July 31” was requested for the companies in the “consortium” made up of: Proton, Delta, Schlager, Loran, Xiamen, Novosi Solution, Zervekas, and Shamrium—all unknowns in the international oil market but now buyers of Venezuelan crude.

The email is revealing. Not only was it sent a month after the U.S. Treasury included Joaquín Leal on the so-called Clinton List of the Office of Foreign Assets Control (Ofac) for considering him the “key conduit” between Libre Abordo and Schlager Business Group to evade U.S. sanctions against the Chavista regime, but it also uncovers that one group controlled numerous companies for the same operation of purchasing and reselling Venezuelan oil.

Although Venezuelan crude oil exports in 2020 were the lowest in decades, recent figures suggest that the alternate mechanism is functioning. Last November, for instance, 24 oil shipments left Venezuela with 639,000 daily barrels of crude and refined products. These volumes are nearly double those of the previous month, October 2020, according to reports from Reuters, even though sanctions against Pdvsa and various shipping lines that register tankers on routes to Venezuelan ports were already in effect.

Previously, the U.S. Treasury had estimated that up to April of last year, Mexican Libre Abordo, part of Saab and Leal’s network, had taken around 30 million barrels from Venezuela and that, before the sanction, the company was concentrating 40% of Pdvsa’s crude exports.

Reuters attributed the November jump precisely to exports via “ghost buyers in Russia.” Several of these unknown companies match those listed in the email sent to Pdvsa and, according to Reuters, were registered in Moscow by OGX Trading, established in March by Sergei Basov, a name that also leads back to Alex Saab.

Basov is a Russian businessman with commercial ties to Betsy Desireé Mata Pereda, a Venezuelan who, as previously revealed by Armando.Info, is part of the corporate structure Saab built to manage the so-called Clap Stores, the retail chain established in Venezuela based on the remnants of the old Bicentennial Markets. Mata Pereda heads the Turkish company Mulberry Proje Yatirim, which replaced the firm registered in Hong Kong with which Saab and Pulido Vargas managed at least two multimillion contracts for supplying Clap and others for supplying medicines from India.

Recently, the news agency reported the emergence of companies registered in the United Arab Emirates as new ghost buyers of Venezuelan oil. In documents viewed by Armando.Info and El País, a firm registered in that jurisdiction appears as responsible for exporting oil to Palestine, in a triangular operation marked by secrecy in the Venezuelan state company. “The staff of the Palestinian embassy requested not to use emails with the company POGC Petroleum and Energy due to limitations caused by Pdvsa’s sanctions. So far, everything has been done in person or via phone, both with the ambassador and with the charge d’affaires,” reads an email from August 12, 2020 sent from the Vice Presidency of Trade and Supply of Pdvsa.

The sophisticated network for commercializing Venezuelan oil included a UAE-registered company to transport crude to Palestine.

The sophisticated network for commercializing Venezuelan oil included a UAE-registered company to transport crude to Palestine.

According to the contract, Pdvsa was to ship between July and August last year 1.8 million barrels of crude from the Merey 16 and Boscán varieties. Payment from POGC Petroleum and Energy FZ-LLC to the Venezuelan state company would be made in dirhams, the official currency of the UAE.

Modus operandi

Both with the Mexican companies Libre Abordo and Schlager Business, as well as with the Russian or UAE firms, the scheme has remained unchanged since mid-2019. The companies acquire oil from Venezuela, sometimes on credit or with discounts. Swissoil Trading, the commodities seller represented by Alessandro Bazzoni, transports it to Asian ports (mainly Singapore), according to numerous shipping manifests reviewed by Armando.Info and El País. Although the company denied to Reuters its involvement in the commercialization of Venezuelan crude, Bazzoni has also used Elemento Ltd, Pdvsa’s allied company in Petrodelta where he co-owns with the recently deceased Oswaldo Cisneros, in this operation.

A precursor of these intentions by Bazzoni can be found in March 2018. The businessman, known for his passion for polo, on behalf of Elemento Ltd, sent a letter to Asdrúbal Chávez, Hugo Chávez’s cousin and then president of Citgo, Pdvsa’s arm in the U.S. In it, he expressed his desire to “participate as a buyer in the bid for products and as a supplier for its crude requirements.” Citgo had not yet come under the control of the interim government of Juan Guaidó.

The documents and communications show that, in most cases, the ships in charge of transportation, both with the Mexican and the Russian companies, were the tankers Lion King, Delta Kanaris, Delta Harmony, A Melody, Perfect, Azimouth, Nichioh, Commodore, Euroforce, and Athens Voyager.

When purchases of Venezuelan oil were still handled by Libre Abordo, it was Joaquín Leal himself who maintained direct communication with Pdvsa. “Dear Libre Abordo S.A de CV team. Pdvsa is waiting for the presentation of your offer for Merey 16 crude, which we are interested in evaluating,” reads an email sent on August 28, 2019, by the International Marketing Department to Leal. Numerous communications, like this one, between the Venezuelan state oil company and the young Mexican entrepreneur, can be found in the documents accessed by Armando.Info and El País.

The response from Libre Abordo arrived in the form of a letter confirming their interest in acquiring the oil. From there, communications began to conduct quality tests on the product and coordinate the ship that would take the crude at Venezuelan ports, either under a ship-to-ship arrangement or directly. At this point, Swissoil Trading, the Swiss commodity company led by Bazzoni, would come into play.

Between mid-August and October 2019, Libre Abordo took nearly 20 million barrels of Venezuelan crude blends like Merey 16, Hamaca Blend, Boscán, and Special Hamaca Blend, as well as fuel oil, according to the papers viewed for this investigation. In June last year, the month Alex Saab was detained and Joaquín Leal sanctioned by the Treasury Department, between Delta and Proton, at least 15 million barrels were taken from Venezuelan ports, mostly of Merey 16 crude.

The documents reveal that Pdvsa’s discounts ranged from 10% to 15%, depending on the destination and market conditions. The Pdvsa invoices disclose that Mexican Libre Abordo was to pay the Venezuelan state company in euros via transfers to bank accounts from Russian banks like Evrofinance and Gazprombank. According to those invoices, on June 19, 2020, just a day after the Treasury Department sanctioned Joaquín Leal and his Mexican companies, Pdvsa billed Libre Abordo nearly 33 million euros for a tanker with just over a million barrels of Special Hamaca Blend crude, and another load of just over a million barrels of the same type of crude for almost 29 million euros. That same day, Pdvsa billed Libre Abordo another 47 million euros for just over 1.8 million barrels of Merey 16 crude.

It remains unclear whether Libre Abordo ultimately paid for all the Venezuelan oil it received from Pdvsa, as when it became public that U.S. authorities were tracking it, the company declared bankruptcy and reported a loss of 90 million dollars. It is clear, however, that the value of the oil received since mid-2019 far exceeds the supposed “humanitarian exchange” that kicked off its business with Caracas, which required it to deliver 1,000 tank trucks and 200,000 tons of corn, valued at 139 million euros and 53,193,900 euros, respectively. “This does not correspond with the amount of oil delivered by Pdvsa, which was resold by Libre Abordo and Schlager Business Group, valued at over 300 million dollars,” warned the Department of the Treasury in June 2019.

Knocking on Pemex’s door

The volume of Venezuelan oil accumulated by Alex Saab, Joaquín Leal, and Alessandro Bazzoni prompted them to offer it to Pemex, the Mexican state oil company and a relevant player in the global hydrocarbons market. On November 18, 2019, Libre Abordo sent an email to Pemex offering two shipments of one million barrels each of Special Hamaca Blend crude from the Delta Harmony and Delta Kanaris ships.

“We have the following two shipments available for sale, which are completely free of any liens, injunctions, attachments, or any similar orders resulting from any arbitration. I am sending you a draft recap to open discussions and propose a call to discuss details,” the email sent by Alexander Rodríguez, on behalf of Libre Abordo, to Pemex’s marketing executives states.

This was not the only attempt to do business with Pemex. Through two other Mexican companies, lacking experience in the oil market but confirming Joaquín Leal’s alliance with Alessandro Bazzoni and Swissoil Trading around Venezuelan oil trading, attempts were made to buy gasoline and other fuels from Pemex. Swissoil Trading did not respond to the interview request sent via email.

In May 2020, the company Promotores del Fomento, initially dedicated to private security under the name Servicios Integrales de Seguridad Privada, offered to buy from Pemex five million barrels of oil, two million barrels of gasoline, and the same amount of heavy fuel oil per month.

During the amendment of the legal name of the company, care was taken that Joaquín Leal’s name did not appear in the records, but that changed nine days before taking their papers to Pemex. Leal appears as the owner of 50% of the shares and Alessandro Bazzoni, the Italian trader linked to Elemento and Swissoil Trading, as the owner of the remaining half.

Joaquín Leal tried to sell the Venezuelan oil captured by Libre Abordo to the Mexican state company Pemex.

Joaquín Leal tried to sell the Venezuelan oil captured by Libre Abordo to the Mexican state company Pemex.

The request to Pemex also shows Philipp Apikian as the director of the Mexican company. Apikian is the owner of Swissoil Trading, the firm that has transported much of Pdvsa’s crude to circumvent U.S. sanctions.

American Richard Rothenberg, acting as director of Elemento in Malta—an offshore paradise in the eastern Mediterranean—is the finance chief of Promotores del Fomento in Mexico. Also mentioned are Chilean Joaquín García as operations chief and Russian Slava Aleksandridi as commercial director. All have held their positions, according to Leal, for at least three years, meaning before the formal existence of his company.

Swissoil Trading even went so far as to extend a commercial reference so that its sister company could secure the deal with the Mexican state firm. “Business between both companies concentrates on high-density oil transactions, as well as maritime shipments to Asia and the Middle East,” states the document, in which it indicates that both firms trade over 100 million dollars every quarter. The letter is signed by Philipp Apikian, director of Swissoil and simultaneously of Promotores del Fomento.

With Swissoil Trading, Joaquín Leal and Alessandro Bazzoni tried to replicate the oil scheme they had established in Venezuela in Mexico.

With Swissoil Trading, Joaquín Leal and Alessandro Bazzoni tried to replicate the oil scheme they had established in Venezuela in Mexico.

This is not the only point that draws attention to the documents presented by Promotores del Fomento. To support its offer to Pemex, Leal accompanied it with a series of recommendation letters and contracts established with unusual partners. For example, there is an agreement with Eastern Refining Limited, the only refinery that Bangladesh Petroleum Corporation has, the state oil company of that Asian country. Also, a contract with Hellenic Petroleum, Greece’s largest refinery, owned by the Athens government and the multimillionaire Latsis family.

According to these agreements, the Mexican Promotores del Fomento would provide the crude, and both Eastern Refining Limited and Hellenic Petroleum would refine it for subsequent resale. In both agreements, it states that the oil would come from “known suppliers,” but in the case of Hellenic Petroleum, there is a quality section that accurately specifies that standards must be met for several Venezuelan blends such as Boscán, Merey 16, Zuata, Mesa 30, and Santa Bárbara. Leal’s company, according to the document, was to deliver the shipments at the port of Hamriya, in the UAE. Leal’s proposal was to take the Mexican oil that he might eventually acquire from Pemex to clients in Russia, China, and India.

“Since January 2019, our company has been working with the commercial division of Promotores del Fomento in activities related to the sourcing and distribution of petroleum products in the Greek local market,” reads a recommendation letter with the letterhead of another partner in Greece, Aegean Oil, a company linked to Dimitris Melissanidis, the former president of the AEK football club in Athens. “Business between both companies ranges around 32 million dollars a year,” it adds.

Forged papers

Among the bank credentials Promotores del Fomento presented to Pemex are three letters of recommendation that appear to have been issued by two Norwegian banks, Instabank and Sparebanken More, and one Swedish bank, Handelsbanken. “It is our opinion that your management has extensive experience in commercial oil activities and is reliable, and that Promotores del Fomento has sufficient financial standing to conduct these commercial activities,” reads the letter stamped by Instabank.

However, these are counterfeit documents, according to all their alleged issuers.

“We are not familiar with the letters presented,” Handelsbanken responded, “they are the result of forgery.” The Swedish bank details that the stamps used are not theirs and that the person signing is not an employee of the bank. “Our company has not issued or provided any of the attached recommendation letters, and therefore they are forgeries,” Aegean Oil responds, stating that it has never had Promotores del Fomento or Leal on its client list.

Hellenic Petroleum, the Greek refinery, also asserts that the “contract” is false, as well as the names of the refinery that supposedly has been the counterparty and the employee who signed it; however, it goes a step further: “We intend to examine the case thoroughly and consider any possibility of taking legal action against anyone who has used our company’s name in bad faith.” The Norwegian banks did not respond to multiple inquiries for comments made by Armando.Info and El País. In the case of the refinery in Bangladesh, the signatory does appear as one of its employees, but its spokespeople also did not respond to authors to clarify the situation. In all letters, it states that Promotores has existed since 2018, even though the Mexican commercial registry indicates that the company appeared almost two years later.

Finally, Pemex rejected Promotores del Fomento’s request to do business on May 27, 2020. The response indicated that the documentation was incomplete and that it lacked its own infrastructure to guarantee the deal. The oil company ruled that Promotores was seeking to benefit as an intermediary in the market, which conflicted with the policies of PMI Trading, Pemex’s arm for international trade that seeks direct deals with interested refineries. The company insisted on processing, but to date, it does not appear in the roster of buyers of the Mexican state-owned company.

In July, weeks after Leal was included in the OFAC blacklist in the U.S. Treasury Department, a purchase request similar to that of Promotores del Fomento appeared before Pemex. This time in the name of Suministradora Bennu, a Mexican company specialized in the electric market, where Leal took his first steps as a shareholder and energy advisor. The businessman had been its advisor for three years, while his sister and employees also handled the management and website of the company.

Leal’s name does not appear in the commercial records of Bennu, but it is one of the companies mentioned in the business portfolio of The Mystic Universe Capital, an investment fund created by Leal in Canada in 2019. The Mystic Universe Capital has only invested in companies linked to Leal, according to its now-defunct website.

Bennu presented Pemex practically the same credentials as Promotores del Fomento to support its request, including letters of recommendation from Instabank and Handelsbanken, and a commercial reference from Aegean Oil, likewise dismissed as counterfeit documents. In this case, the proposal was to purchase 20.8 million barrels of fuel oil over twelve months. The first shipments were to begin with cargoes of 700,000 barrels and continue with mass deliveries of 2.8 million barrels, intending to send them to markets in Asia.

Enrique Woodhouse, the owner of Bennu, acknowledges that he had a commercial relationship with Leal, but insists he was not aware of this request and that his company has nothing to do with the oil market. He adds that he broke off from his former partner after the Treasury sanctions became known.

Pemex would ultimately also reject Bennu’s request, arguing that it did not have sufficient supplies to fulfill the order, government sources said. Early June, Promotores del Fomento was liquidated, according to the Mexican commercial registry. The person in charge of closing the company was Adán Jimenez Alfaro, Leal’s maternal uncle.

The idea of buying gasoline—as attempted with Pemex—had been in the plans of Alex Saab and Joaquín Leal since the start of their oil business with Pdvsa in mid-2019. These intentions became more explicit as fuel scarcity worsened at Venezuelan service stations. Thus, under another corporate identity, that of Grupo Jomadi Logistics & Cargo, a Mexican company linked to Libre Abordo and Schlager Business Group, they proposed a swap contract with the Venezuelan state company. The deal involved the exchange of millions of barrels of Venezuelan Merey 16 crude for Mexican 95-octane gasoline.

The supply contract was to run from March 25 to July 25, 2020. The Venezuelan oil was to be transported to Turkish ports. Sources knowledgeable of the operation assert that in the end the contract was not executed, prompting Alex Saab to design a scheme to import gasoline from Iran starting mid-last year, something his lawyer, former Spanish judge Baltasar Garzón, recently acknowledged. “In April 2020, when the Covid-19 epidemic wreaked havoc on the Venezuelan economy, he was also tasked with acquiring desperately needed gasoline from Iran. Shortly after expanding his mission, special envoy Saab traveled to Iran and negotiated the delivery of eleven million gallons of gasoline, which arrived in May,” Garzón stated to El Espectador from Bogotá.

The stop in Cabo Verde on June 12 during a trip to Iran, where Alex Saab negotiated the purchase of gasoline for Venezuela, cost the Colombian businessman his arrest.

The stop in Cabo Verde on June 12 during a trip to Iran, where Alex Saab negotiated the purchase of gasoline for Venezuela, cost the Colombian businessman his arrest.

However, it would be an unfortunate stop on the island of Sal in Cabo Verde, in June 2020, right in the middle of one of those trips to Tehran for procurement that Saab was captured. He now awaits his possible extradition to the United States, a fate from which perhaps his attempted maneuvers will not save him—some as imaginative as his belated designation as Venezuela’s Ambassador to the African Union—as well as the financial strategies and legal entities that Saab himself devised to continue doing business with Maduro.